Throughout the history of the Supreme Court, race and religion have played important roles in the nomination and confirmation of Supreme Court justices. In some instances (such in the case of Louis D. Brandeis) opposition to appointments were triggered by the nominees’ religion; on other occasions, the nominee’s race or religion was a positive factor in their selection and confirmation (Clarence Thomas and Sonia Sotomayor).

Until recently, I was unaware of any circumstance in which the racial and religious composition of a justice’s Chamber’s staff was considered relevant to that justice’s fitness to hold office. While doing research about Supreme Court messengers, however, I stumbled across a cluster of newspaper articles from September of 1937. These articles reported that Leon A. Smallwood, Sr. had been appointed to be the messenger to newly-confirmed Supreme Court Justice Hugo L. Black. The news accounts added that Smallwood was both Black and Catholic.

The fact that newspapers around the country focused on the routine appointment of heretofore anonymous court staff was unusual. It was, however, the articles’ discussion of Smallwood’s race and religion that piqued my curiosity. Intrigued, I searched for additional articles about Justice Black’s hiring practices. What emerged from my research is a disturbing story of how the race and religion of Black’s employees was strategically used to push back against claims that the Alabama Justice was a racist anti-Catholic who should be removed from the Court.

On August 12, 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt nominated Alabama Senator Hugo L. Black to replace the retiring Justice Willis Van Devanter. While some of Black’s Senate colleagues knew that he had been a member of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, Roosevelt later claimed to be unaware of Black’s Klan affiliation. Black’s nomination was not universally embraced by his fellow senators, but out of senatorial courtesy they swiftly voted to confirm him. On August 18, 1937, one day after the Senate vote, Black took the oath of office. According to biographer Howard Ball, Black later explained why he wanted to be quickly sworn in.

I wasn’t taking any chances. I knew that my enemies in big business and the press would inflame the public against me so much that they might get a judge to enjoin me from taking the oath. After I had taken the oath, my enemies would have to impeach me for something I had done since taking the oath of office.[2]

With the hindsight of history, Ball concludes that Black’s decision to immediately take the oath was “prudent.”

Shortly before leaving for a vacation in Europe, Black hired one of his Senate office secretaries – Anne Butt – to work in his new Chambers (a few newspapers referred to her as “Annie”). Black biographer Roger K. Newman writes that Butt’s selection was strategic.

He needed a secretary at the Court. Since rumors about some Klan affiliation were still circulating, he had to make a clean break with his past, and to Black this meant hiring a Catholic. Esther Wood had worked for him for nearly twenty years…[b]ecause she was Protestant, however, he came up with one of his most preposterous stories: he told her she could not go to the Court with him because the Alabama Democratic Executive Committee had passed a resolution that it had to approve his choice. Then he asked one of his young secretaries if she would serve at the Court. She was Catholic. But she wanted to return to Mobile to get married, and declined. So he asked another assistant [Anne Butt] – she too was Catholic. She readily agreed.[3]

On August 26, 1937, the newest member of the Supreme Court boarded the liner City of Newport News. Joined by his wife, Josephine, Justice Black departed for a European vacation. Newspapers reported that he would be back in time for the opening of the Supreme Court’s October Term.

Two weeks later, the Pittsburgh News Gazette published its first in a series of stories about Justice Black’s membership in the Ku Klux Klan. Reporter Ray Pringle claimed that not only was Black a member of the Klan from 1923 to 1925, but that, after resigning from the Klan, he was later awarded a “golden passport” and given life-time membership. Outrage followed, with newspaper editorial boards and politicians calling for Black’s resignation. Now in England, Justice Black refused public comment.

Three days after the Klan revelations, the first story appeared about the religious make-up of Black’s new Supreme Court staff. In defending the Justice against charges of religious intolerance, Black’s former Senate campaign manager W. Cooper Green listed off Catholics whom Black had appointed to various offices. “On top of this, he said, Black’s personal stenographer is Miss Annie Butt of Birmingham, a Catholic, and the justice, he added, is taking Miss Butt with him as his stenographer to his supreme court office.”[4]

Approximately a week later, a flurry of articles appeared regarding Leon A. Smallwood, Sr. – Justice Black’s new Supreme Court messenger. “Court Appoints Negro Catholic as Black’s Aide,” reported the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.[5] “Catholic, Negro on Black’s Staff” was the headline in the Wilmington News. “Catholic Negro Gets Assignment to Black” proclaimed Public Opinion. “Klansman Black Is Assigned Catholic Negro Messenger,” stated the Port Huron Times Herald.

Almost all messengers at the Supreme Court were black men, so Smallwood’s race was not newsworthy. (The novelty of a Catholic stenographer is harder to assess as the religions of the handful of female assistants who worked for justices in the 1930s is not known.) The newspaper articles, however, did not cite the source of their information about Smallwood’s religion. If the Supreme Court released such information, however, it would have been at the behest of Justice Black.

While newspapers had not offered their readers details on Anne Butt, they now provided a slew of materials on Black’s second hire. “[H]e is a middle-aged and intelligent-looking colored man,” reported the Lancaster New Era. “He has been good-natured about it [the Klan controversy] and obviously pleased at his new appointment, but Frank Green, Marshall of the Court, has not.” And what was the source of Green’s discomfort?

Worried over reports that he appointed Smallwood to the position as a joke on Justice Black, Mr. Green has kept the Negro almost under lock and key for the past two weeks. Smallwood has been given work only in the Marshal’s office, and instructed to talk to no one even when he goes home.[6]

Some newspapers assumed that Smallwood’s appointment was a “joke” by the Marshal’s office. Yet even if Black himself had not intentionally chosen Smallwood for his religion, the Chicago Tribune chortled that “[c]hance played an ironic trick on Mr. Justice Black.”[7] Whether it was chance or intentional, the appointment was a strategic opportunity for Black’s supporters to argue that a justice with two Catholic assistants could hardly be considered anti-Catholic.

The relationship between Smallwood’s race and religion and the brewing Klan controversy did not escape the notice of some reporters. “Leon Smallwood is the name of a wonderful man,” commented the Pantagraph. “He was appointed as court messenger for Justice Hugo Black. Being a Negro and a Catholic, he thus impersonates a double denial of Ku Klux charges against Black.”[8] The Honolulu Star-Bulletin was a bit more circumspect; after noting Smallwood’s race and religion in the first paragraph of its article, the second paragraph stated:

Justice Black has been accused of membership in the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan stands for supremacy of the white race and is opposed to domination in the United States by any foreign power, including the pope as head of the Roman Catholic church.

One person reading the stories about Black’s Catholic secretary and messenger was Bernard Monaghan, a recent Harvard Law School graduate who himself was travelling to England. Harvard Law School Professor Felix Frankfurter cabled Monaghan on Justice Black’s behalf and offered him a clerkship position for the new Justice. Frankfurter suggested that, when Monaghan arrived in England, that he discuss the clerkship offer with political scientist Harold Laski. When the two men met, Laski told Monaghan to take the clerkship. “Black, a politician with a checkered past, was striving to become a liberal, Laski said, and it was Monaghan’s duty to help him.”[9] Monaghan, however, declined the offer on the grounds that the news accounts of the Catholicism of Justice Black’s staff “just smelled too much.”[10]

As the fury over Justice Black’s Klan membership continued, the Blacks finished their vacation and returned to the United States. When their ship docked at Norfolk, Virginia on the morning of September 29, almost one hundred newspaper reporters were there to meet them. Faced with renewed calls to resign, Justice Black decided to rebut the allegations by giving a nation-wide radio address on October 1.

In his remarks, Justice Black cast himself as a victim, telling his audience that “[a]n effort is being made to convince the people of America that I am intolerant, and that I am prejudiced against people of the Jewish and Catholic faiths, and against members of the Negro race.” Acknowledging that these allegations stemmed from his Klan membership, Black informed his audience that his Klan membership was short-lived and was not a reflection of his values or beliefs.

I number among my friends many members of the colored race. Some of my best and most intimate friends are Catholics and Jews. Shortly after I moved to Birmingham, more than a quarter of a century ago, I formed one of the most valued friendships of my life with a son of Jewish faith [Herman L. Beck]. He was one of my closest associates and strongest political supporters. Months of our lives were spent together, much of the time in his home. He stood so nearly in the place of a father to me that while in the Army in 1918 I designed this trusted Jewish friend as sole executor of my will. In my campaigns for public office his counsel and assistance were always mine. His widow who was a guest in my home at the recent inauguration of President Roosevelt was one of the first to congratulate me upon my nomination to be a Justice of the Supreme Court.[11]

Amongst the forty million listeners was Leon Smallwood. Although he had avoided the press, he offered a brief public comment on the radio address – calling it “a fine speech.”[12]

While Black’s radio address suffered from self-pity and hyperbole, he was not exaggerating when it came to his strong friendship with Birmingham businessman Herman Beck. Biographer Newman writes that Beck first met Black in 1926, when the future justice moved to Birmingham. “He took an instant liking to Hugo,” and soon the older businessman was serving as a friend and mentor. Late in life, Black would comment that “Herman Beck was one of the best people ever to do, the best friend I ever had.”[13] In a 1967 interview with the New York Times, Black asserted that it was his Jewish friend who urged him to become a member of the Klan:

The Klan in those days was not what it became later. There were a few extremists in it, but most of the people were the cream of Birmingham’s middle-class. It was a fraternal organization, really. It wasn’t anti-Catholic, anti-Jewish, or anti-Negro. In fact, it was a Jew, my closest friend, Herman Beck, who asked me to join, and said they needed good people in the Klan. He couldn’t be in it, of course, but he wanted to keep down the few extremists.[14]

Like many of Black’s statements about his Klan membership, the above quotation does not hold up to careful scrutiny; if the Klan in the 1920s was not anti-Jewish, then why wasn’t Beck allowed to join?

Justice Black could not pause to catch his breath after this public effort at damage control. The radio address was on Friday, the October Term started on Monday, and he still needed a law clerk. That weekend, Black hired a Harvard Law School graduate from Birmingham, Alabama named Jerome Cooper. At the time, Cooper was clerking for federal district court judge David J. Davis in Birmingham. Given that Black and Davis were friends as well as former law partners, it’s likely that the Justice consulted with Davis before poaching his clerk. Cooper had never met Black, but the surprised young man accepted the offer. He made a “hasty journey” from Alabama to Washington, DC.[15]

On opening day, the Court issued a press release about Justice Black’s newest law clerk. The announcement was highly unusual for two reasons. First, the Supreme Court was not in the practice of notifying the press regarding law clerk hiring decisions. Second, the press release included the statement that Cooper “is of the Jewish faith, ”[16] the first time it had publically announced the religion of a law clerk. (Cooper was far from being the first Jewish law clerk: at least a dozen had served by 1939.) While Justice Black’s damage control continued, there is no direct evidence that he directed the Marshal’s Office to release information on Cooper’s religion. That being said, it is almost impossible that the announcement would have included such information without Justice Black’s explicit approval.

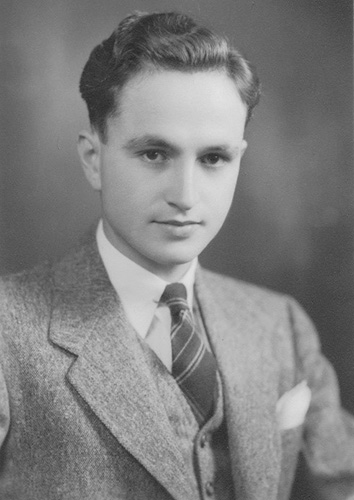

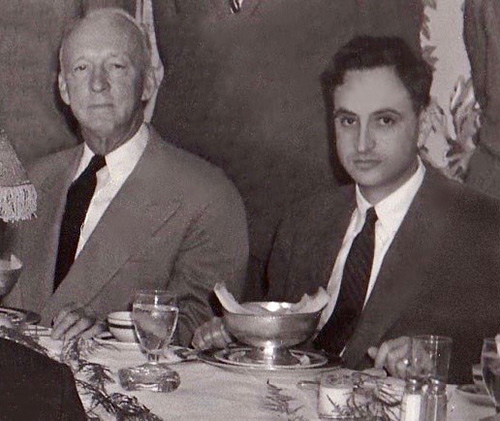

The Court’s announcement triggered another round of articles with offensive headlines. “Justice Black Appoints Jew as Law Clerk.”[17] “Black Selects Jew, Catholics.”[18] “Jew is Appointed Law Clerk for Justice Black.”[19] “Black Selects Jew.”[20] “Black Names Jew as His Law Clerk.”[21] “Black Ads [sic] Jew to Personnel.”[22] “Black Picks Jew, 2 Catholics and Negro as Aides!”[23] In case readers didn’t believe the reports that Justice Black had hired both a Catholic and a Jew, newspapers published a picture of Anne Butt and Jerome Cooper having dinner together. One newspaper identified them as “Jerome Cooper, Jew from Birmingham, Ala., and Anne Butt, Catholic from Birmingham, Ala.”[24]

As with the hiring of Smallwood, some newspapers questioned the Justice’s motivations in selecting a Jewish clerk. “It has been revealed that by ‘mere coincidence’ Justice Hugo L. Black has now on his working staff a Jew, and a negro who is at the same time a Catholic,” the Harvard Crimson tartly noted.[25] The Evening Report added that Cooper’s appointment, following in the steps of the hiring of Butt and Smallwood, “lent a tinge of irony as Black, one time Ku Klux Klansman, took his seat at the Supreme Court.”[26]At least one newspaper reporter sardonically suggested that the racial and religious minorities in Justice Black’s chambers would keep the Justice in line.

Assuming no religious arguments break out in the Black offices – which would be just too bad – this set-up would seem to help bear out Black’s radio assertion that there is no intolerance in his soul. At any rate, those groups, the hatred of which won infamy for the Klan, will have representatives in a strategic spot where they can keep a careful eye on the justice in case he should ever again yearn for a white robe.[27]

Anne Butt, Leon Smallwood, Sr., and Jerome Cooper never publicly addressed the claims that Hugo L. Black deliberately hired them to rebut claims that he was a racist or intolerant of Jews and Catholics. Nor do family members of the late Jerome Cooper recall him ever talking about the role that religion may have played in his clerk selection. If Justice Black did find it useful to his reputation to have a messenger who was Catholic, Smallwood’s utility quickly faded – although the historical records are a bit unclear, it appears that, at most, Smallwood worked for only a few months before being assigned to Justice Brandeis. (He would later serve as William O. Douglas’ messenger.) Smallwood was soon replaced by Spencer Campbell, Black’s long-time chauffer from Alabama. (His sister, Lizzie Mae Campbell, was Black’s cook who also moved to Washington, to continue to prepare his favorite Southern dishes.) Campbell served as messenger from 1938 until 1971, when Justice Black retired.

Although Hugo L. Black was originally lukewarm about the idea of serving on the Supreme Court, he soon embraced his nomination and fought hard against repeated calls for his resignation. While the historical record is mixed, many historians believe that Senator Black hid his Klan membership from President Roosevelt, did not stop fellow senators from making inaccurate statements about his involvement with the Klan, and falsely claimed to have ended his membership with the Klan in 1925.

Justice Black’s strategic behavior, however, extended beyond minimizing his involvement with the Klan. It appears that he strategically hired Butt and Cooper because of their religious faith, and, moreover, took steps to make sure that the religious and racial backgrounds of all three staff members were publicly disclosed. The only explanation for Black’s behavior was that he wanted to counter charges that he embraced the Klan’s prejudices against blacks, Jews, and Catholics. While it is impossible to determine the extent to which this strategy helped quell the fury over his Klan membership, one can safely conclude that this was not Hugo L. Black’s finest hour.

[1] Peppers is the Fowler Professor of Public Affairs at Roanoke College as well as a visiting professor of law at the Washington & Lee School of Law.

[2] Howard Ball. Hugo L. Black: Cold Steel Warrior (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996): 95.

[3] Roger K. Newman. Hugo Black: A Biography (New York: Pantheon Books, 1994): 245. Newman’s claims are based on interviews with Esther Wood Quantock and Anne Butt Daniel.

[4] “F.R. Advisers Demand Black Resign: Urge Justice to Quit at Once.” Akon Beacon Journal, September 16, 1937.

[5] “Court Appoints Negro Catholic as Black’s Aide.” The Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 23, 1937.

[6] “Black’s Assistant.” Lancaster New Era, October 1, 1937.

[7] “Negro Catholic is Messenger.” Chicago Tribune, September 24, 1937.

[8] The Pantagraph (Bloomington, Illinois), October 10, 1937.

[9] “The Road Not Taken.” Fortune Magazine, Volume 16, No. 1 (July 1, 1975): 45.

[10] Newman. Hugo Black, 267.

[11] Newspapers raced to identify this mysterious widow, later identified as Mrs. H.L. Beck of Birmingham, Alabama. A copy of Mrs. Beck’s telegram was helpfully provided to the press. “Friend Identified: Jewish Widow Congratulated Black.” The San Francisco Examiner, October 2, 1937.

[12] “Colored Employe [sic] Lauds Boss Black.” Lansing State Journal, October 3, 1937.

[13] Newman. Hugo Black, 126.

[14] Id. at 97.

[15] “Clerk, Secretary, Messenger.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 10, 1937.

[16] “Black Selects Jew, Catholics.” Johnson City Chronicle, October 5, 1937.

[17] “Justice Black Appoints Jew as Law Clerk.” Sioux Center News, October 7, 1937.

[18] “Black Selects Jew, Catholics: Negro Also Member of Office Force Serving Associate Justice.” Johnson City Chronicle, October 5, 1937.

[19] “Jew is Appointed Law Clerk for Justice Black.” Evening Report (Lebanon, Pennsylvania), October 4, 1937.

[20] “Black Selects Jew.” Cincinnati Inquirer, October 5, 1937.

[21] “Black Names Jew as His Law Clerk.” Times Dispatch (Richmond), October 5, 1937.

[22] “Black Ads [sic] Jew to Personnel.” Red Bluff Tehama County Daily News, October 6, 1937.

[23] “Black Picks Jew, 2 Catholics and Negro as Aides!” News-Palladium (Benton Harbor), October 5, 1937.

[24] “Black’s Staff at Dinner.” Daily Tribune (Wisconsin Rapids), October 13, 1937.

[25] “Harvard Jew Appointed by Hugo Black to Be Law Clerk. Harvard Crimson, October 5, 1937.

[26] “Jew is Appointed Law Clerk for Justice Black.” Evening Report (Lebanon, Pennsylvania), October 4, 1937.

[27] “Jewish Lawyer Will Be First to Face Black: Will Argue Government Side in Duke Power Company Fight.” Grand Island Daily Independent, October 22, 1937.