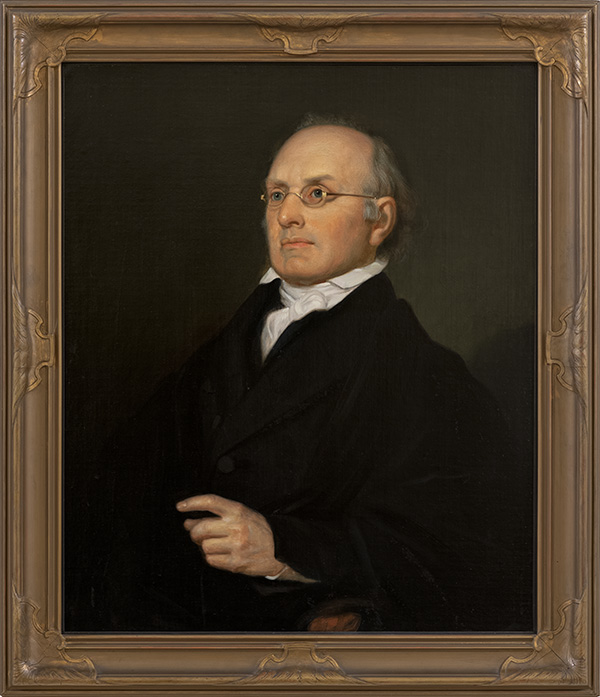

The poet-at-heart who became the youngest Associate Justice of the Supreme Court and a leading Constitutional scholar whose work continues to influence modern interpretations of law.

Joseph Story was born in Marblehead, Massachusetts on September 18, 1779. His father, Elisha Story, was a prominent local doctor and his mother, Mehitable Pedrick Story, was a homemaker. Joseph was one of eighteen children and the oldest of his father’s second marriage. Growing up, Joseph was inspired by the accomplishments of his father and grandfathers. Dr. Story was a notable participant in the Boston Tea Party and his father served in the British Vice Admiralty Court in Boston and became a clerk of the American Navy Board. Mrs. Story’s father helped to stop a British raid on a stockpile of munitions in Salem, Massachusetts in 1775, a few years before the American Revolution.

Joseph received his primary education at the Marblehead Academy but left for early admission to Harvard after a conflict with another student. He enrolled in 1795 and met with much academic success at the expense of his personal health. Though Joseph graduated second in his class, he worked himself ill. He would struggle with various stomach ailments the rest of his life. Upon graduation, he returned home and rest gradually helped his health improve. He apprenticed with notable attorney Samuel Sewell. After Sewell was appointed to become a state judge, Joseph finished his legal studies with attorney Samuel Putnam in Salem and passed the bar in 1801.

Despite his time and effort studying the law, Joseph’s heart was in reading and writing poetry. When his published work was not well received, however, he decided to concentrate all his efforts on his law career. He married Mary Linde Fitch Oliver in 1804, but she died a mere seven months into their marriage. Joseph’s father died two months after Mary, devastating the young lawyer. Joseph threw himself into his law practice but his political affiliations and Unitarian religious beliefs were unpopular in Federalist dominated Massachusetts and he initially had very few clients. In time, he began to attract more clients through his success in the courtroom and political association with a prominent local shipping businessman, Jacob Crowninshield.

From 1805-1811, Joseph tried his hand serving in various positions in the Massachusetts and federal Legislature, eventually being briefly named Speaker of the House for the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1811. His talents led to his first opportunity to argue a case before the Supreme Court: he argued Fletcher v. Peck in 1810. The Court unanimously sided with John Peck, Joseph’s client, in a ruling which held a state law unconstitutional for the first time.

During his rather busy career, he married Sarah Waldo Wetmore, the daughter of a Boston Judge. Though the couple had seven children together, only two, Mary and William, survived to adulthood. His son William Wetmore Story became a famous sculptor and created numerous works–of which, a bust of his father, is on display in the Harvard Law School Library.

In 1810, Associate Justice William Cushing died, creating a vacancy on the Supreme Court. After much consideration, President James Madison nominated 32-year-old Joseph Story to the Supreme Court. Confirmed by the Senate in November 1811 and taking the oath of office in February of 1812, he remains the youngest Associate Justice to serve in Supreme Court history. President Madison, a Democratic-Republican, may have expected Joseph’s judicial philosophy to differ from Justice John Marshall, who had been nominated by Federalist President John Adams. Despite his earlier political learnings of states rights over federal authority, Joseph, however, embraced Marshall’s vision of the Supreme Court as protecting and advancing the power of the Federal government. Though they did not always agree, Joseph and John became close friends and allies during the 23 years they served together.

Joseph wrote several notable opinions for the Court that were instrumental in asserting and protecting the supremacy of the Constitution and federal law. For example, in Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1816), Joseph expanded the Supreme Court’s authority by recognizing its appellate authority to reverse the decisions of state courts. Later, in his last well-known opinion Swift v. Tyson (1842), Joseph’s majority opinion strengthened federal judicial authority by ruling that federal courts could develop federal common law for commercial cases.

Joseph was an ardent nationalist, but he was also vehemently against slavery even though it threatened the unity of the country. For instance, he wrote the Court’s opinion in the 1841 Amistad case refuting the Spanish government’s claims that the captives transported from Africa by ship were property. He ordered that the men must be set free: “supposing these African negroes not to be slaves, but kidnapped, and free negroes,… and the United States are bound to respect their rights….” The next year, however, he had to make a choice between his devotion to nation building or opposing slavery. In his opinion in Prigg v. Pennsylvania, he reinforced the supremacy of the federal Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 over state laws that would have protected enslaved people who had escaped slavery. The decision overruled state laws in Pennsylvania and allowed enslavers and slave catchers to capture enslaved people who had escaped and also jeopardized the freedom of free black people living in the north.

In the 1800s, each Justice was assigned to one of the regional judicial circuits in addition to serving on the Supreme Court. They spent six to nine months each year away from their homes and families, traveling to various towns hearing cases. The conditions they faced on unpaved dirt roads were often dangerous and lacked the comfort one might expect for a member of the nation’s highest court. Joseph was assigned to the New England circuit and traveled over 2,000 miles holding court in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Hampshire and Maine twice a year. On March 5, 1822, Joseph was severely injured in a carriage accident and treated for his injuries with bloodletting, a common medical practice at the time.

Off the bench, Joseph found time to pursue his interests in higher education and writing–this time about the law rather than poetry. After serving in various roles with his alma-mater Harvard, he joined the law faculty in 1829. According to several accounts, Joseph was never happier than when he was teaching his students at Harvard. He also wrote nine books on the philosophy and legal bases of law–of which, Commentaries on the Constitution, was so successful it was translated into multiple languages. In fact, future Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes observed that Story had “done more than any other English-speaking man in this century to make the law luminous and easy to understand.” Joseph’s brilliant writing helped supplement and eventually surpass his annual salary of $4,500 (approximately $148,000 in modern currency), which he complained was much less than a good lawyer earned.

When his longtime friend and colleague John Marshall died in 1835, Joseph wanted to succeed him as Chief Justice, but President Andrew Jackson appointed Roger B. Taney instead. Chief Justice Taney, along with President Jackson’s four other appointees, brought a more states’ rights ideology to the Court. Though many thought he would retire, Joseph instead chose to remain and attempt to defend the nationalism he and the Marshall Court had embraced. Although many of the more radical reforms expected by the Jackson nominees failed to materialize, Joseph had grown weary. His struggles with his poor health and the tragic deaths of his children weighed on him. He died of an illness on September 10, 1845 before he could announce his impending retirement. Joseph Story’s written works, including his Court opinions, left a lasting impact on American jurisprudence. His writings advanced the theory of the supremacy of federal law. Justice Joseph Story is remembered as a serious constitutional and legal scholar whose nationalist vision of federal law was instrumental in strengthening the nation.

Key Vocabulary:

- Munitions: military weapons, ammunition, and other supplies.

- Apprenticed (Apprenticeship): a paid job where the employee gains valuable experiences through on the job training and mentoring from an experienced professional.

- Passed the bar: a lawyer’s successful completion of all the requirements to practice law. These requirements have changed throughout history.

- Unitarian: a member of a religious group, often a branch of Christianity that does not believe in the Holy Trinity.

- Federalist: a member of one of the earliest American political parties who supported a strong central government.

- Democratic-Republican: a person who supports personal liberty, states’ rights, and agrarian interests (farming).

- Jurisdiction: the power and authority of a court.

- Supremacy: having power and authority over someone or something.

- Opinions: written explanations describing the outcome of a case.

- Ardent: enthusiastic or passionate.

- Amistad: United States v. The Amistad (1841) is a freedom suit case resulting from a rebellion of illegally captured Africans aboard a Spanish ship.

- Federal Common Law: law developed by the federal courts rather than state courts.

- Bloodletting: the purposeful removal of a patient’s blood in an effort to promote healing.

- States’ rights: emphasizes the power of individual states over a stronger centralized government.

- Nationalism: support for one’s own nation often at the exclusion of others. Jurisprudence: the theory of law, a legal system.

Discussion Questions:

- How did Joseph respond to personal and professional setbacks?

- Which of Joseph’s mentioned opinions do you believe is the most important? Explain.

- What can you infer from Joseph’s off the bench employment?

- What conclusions can be drawn about Joseph’s influence on the Supreme Court?

Special thanks to scholar and author Professor William Davenport Mercer, Jr. for his review, feedback, and additional information.

Sources:

- Clare Cushman, The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies 1789-2021, (Sage Publications, Inc., 2013) pp. 76-79.

- “Joseph Story.” Oyez, www.oyez.org/justices/joseph_story. Accessed 24 Feb. 2023.

- Melvin Urofsky, The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary (New York: Garland Publishing, 1994).

- Paul Finkelman, “Prigg v. Pennsylvania: Understanding Joseph Story’s Pro-Slavery Nationalism,” Journal of Supreme Court History, 1997, no. 2 (1997): 51-64.

- William W. Story, Life and Letters of Joseph Story, (Boston: Little & Brown, 1851).