Riding circuit was almost always unpleasant, but sometimes involved accidents such as an overturned carriage as illustrated in the drawing. Library of Congress

Exactly 230 years ago today, on August 9, 1792, the members of the Supreme Court sent a letter to President George Washington. Although unusual today, such a letter may be understandable historically as the country was on its first legs, and trial and error exposed the need for changes. It was a letter appealing to the President to present to Congress their request to relieve the Justices from the burden of “riding Circuit” which was to hold Court twice a year in each of the three Circuits created by the Judiciary Act of 1789.

Congress had conceived the concept of riding circuit with several things in mind. First, it was a way to save money by not appointing additional judges. It also afforded a way for an official from the capital to get beyond the urban centers of government and to learn what was going on in the country beyond the cities. In addition, in a time well before radio and television and other means of speedy communication, it provided a way to report to local citizens on what the federal government was doing. This was accomplished by lectures to grand jury members in which the Justice could articulate things like the responsibilities of citizens, as well as commenting on what the government was doing in the capital.

The letter laid out the concerns of the Justices politely, but firmly. “We really, Sir, find the burthens laid upon us so excessive that we cannot forbear representing them in strong and explicit terms.” Included with the letter was a “representation” detailing their concerns and reasons for seeking to end the practice of riding circuit. A copy of the “representation” was recorded in the records of the Senate Records of Legislative Proceedings. It appears from the text of the letter that it had been the expectation of the Justices that the circuit riding duties would be of a temporary nature, until such time as Congress could devise another solution. This was made clear in the first paragraph which reads in part: “that when the present Judicial arrangements took place, it appeared to be a General and well founded opinion, that the Act then passed was to be considered rather as introducing a temporary expedient, than a permanent System, and that it would be revised as soon as a period of greater leisure should arrive.”

The complaint diplomatically noted that the Justices were aware that the intervening sessions of Congress had been occupied with affairs of great moment, and the Justices had not thought it appropriate to divert their attention to other matters, but that as Congress had not revisited circuit riding yet they felt compelled to ask Congress to reconsider the matter and find a way to relieve the Justices of that duty. They outlined the burdens placed upon them:

“That the task of holding twenty seven circuit Courts a year, in the different States, from New Hampshire to Georgia, besides two Sessions of the Supreme Court in Philadelphia, in the two most severe seasons of the year, is a task which considering the extent of the United States, and the small number of Judges, is too burthensome.

That to require of the Judges to pass the greater part of their days on the road, and at Inns, and at a distance from their families, is a requisition, which, in their opinion, should not be made unless in cases of necessity.

That some of the present Judges do not enjoy health and strength of body sufficient to enable them to undergo the toilsome Journies through different climates, and seasons, which they are called upon to undertake; nor is it probable that any set of Judges, however robust, would be able support and punctually execute such severe duties for any length of time.”

Justices often passed through rough terrain such as this swamp located near Antietam, VA. (New York Public Library Digital Collection)

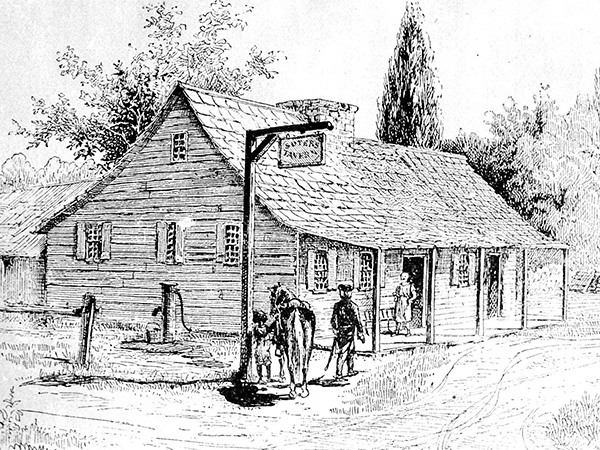

This drawing shows a typical tavern of the the 1790s. Taverns provided, meals, lodging, stabling for horses, but little privacy or comfort. Library of Congress

In modern terms, it may not seem that traveling the circuit is such a burden, but in the 1790s roads were primitive, and in some areas essentially non-existent. There were few bridges requiring travelers to ride through streams and rivers or perhaps find a ferry boat. Travel was accomplished on horseback or by horse drawn vehicles with scant or no protection from the elements in inclement weather. The end of the day’s journey usually provided very little comfort or relief. Housing options were limited to inns which varied a great deal in quality and frequently had poor sanitation and little or no privacy. Food and drink available varied drastically from location to location as well. The only relief was when a Justice was able to stay at the home of friends or family. When staying at an inn Justice Cushing once shared a room with twelve other men. Justice James Iredell complained that on one occasion he “suffered” when he was he was relegated to sleeping in “a room with five People and bed fellow of the wrong sort.” While riding circuit in 1790 with Justice Rutledge, Iredell expressed shock because “I scarcely thought there had been so much barren land in all America.” In 1791, Iredell protested to Jay about his reappointment to the Southern Circuit, recounting that he had not only ridden 1900 miles in 1790, but also he was involved in litigation in North Carolina. He suggests that the circuits should be rotated between Justices, but no action was taken on that suggestion. Justice William Cushing wrote Iredell to commiserate noting that he too suffers from circuit duty and suggested that Iredell change circuits with Justice Blair. In 1792, Justice Iredell was in a road accident which resulted in a severe injury to his leg. He was later robbed while riding circuit. Chief Justice Jay kept a journal in which he recorded his travels and complaints. He complained of the long separation from his family as well as the poor conditions of travel and housing associated with the assignments. Justice Cushing described the situation as sentencing the Justices to “perpetual Itineration.”

These circumstances prompted the Justices to implore the President to present to Congress their request to address these problems. According to the records of the Senate Records of Legislative proceedings, President Washington did so in November of 1792. But there was no immediate action, and in January, Justice Thomas Johnson, citing health problems, resigned from the Court. Most believed it was because he did not want to ride circuit.

In 1793, Congress did amend the law to reduce the number of Justices riding each circuit from two to one. The idea was that in each court season, one Justice would be able to stay home and rest. In practice however, it often did not work that way as substitutions were necessitated due to the illness of another Justice.

The records for 1794 show that Justice Iredell was too ill early in the year to attend the Court’s February session. In August of that year, he refused to ride the southern Circuit in place of Justice Wilson observing that he had been forced to cover that enormous circuit five times over a four year period. His health broken, Justice James Iredell died in his hometown of Edenton, NC in 1799 at the age of 48.

Circuit riding continued until 1911, with a short respite in 1801 when Congress passed an act to abolish the practice. At that time, it also established circuit courts whose judges did not include the Supreme Court Justices. But that solution did not put a permanent end to circuit riding by Supreme Court Justices. Indeed, the area to be travelled increased as the country grew, but the travel was alleviated in part by better means of transportation such as trains and ships. But the pleas of the Colonial era Justices did not bring them much relief as they continued to battle difficult travel conditions, outbreaks of contagious diseases, and other hardships.