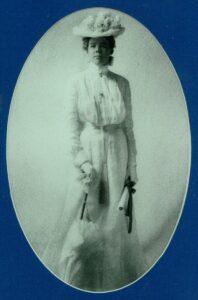

In March 1909 Kansas lawyer Lyda B. Conley brazenly wrote to Chief Justice Melville Fuller. Her petition asking for an injunction against Congress’s authorization of the proposed sale by the Secretary of the Interior of her Wyandot tribe’s burial ground had been docketed in October 1907. She was waiting for an argument date. Conley admonished Fuller: “With me, time is money, and I cannot afford to spend either in idleness.” Indeed, she was so poor that she had struggled to pay the filing fees and the cost of printing materials necessary to file her Supreme Court appeal. Eking out a legal practice representing Wyandot friends in routine contract and property disputes was not enough. She took a job teaching telegraphy to survive. Lyda and her two sisters also spent their time holding vigil over the graves of their ancestors, including their mother, father, and older sister Sallie, who died as a teen. (The sisters lived in a nearby shack and kept off cemetery trespassers with a shotgun.) The Supreme Court notified her in December that oral argument was set for January 14, 1910.

Accompanied by her sister, Lena, Lyda took the train to Washington. Unnetworked, she struck out finding a lawyer who would vouch for her admission to the Supreme Court bar. Most women advocates of that era had attended the same law schools and moved each other’s admission; Lyda had been the first woman admitted to the Kansas Bar Association in 1902. She plowed ahead “pro se” (arguing as a plaintiff not as an attorney), telling a reporter: “No lawyer would plead for the grave of my mother as I could.” Her papers include her handwritten account of her remarks to the justices: she spoke eloquently at the podium about her tribe’s history and setbacks. Radical for her time, Conley articulated both the notion that the burying grounds of American Indian tribes are sacred and deserve federal protection and that descendants of signers of a treaty with the federal government have standing to enforce the treaty’s provisions. She wrapped her argument in patriotism: “I cannot believe that this is superstitious reverence, any more than I can believe that the reverence every true American has for the grave of [George] Washington at Mount Vernon is a superstitious reverence.”

The Court ruled two weeks later in Conley v. Ballinger (1910). Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes was careful in his unanimous opinion to reassure Conley that the justices had deliberated carefully: “For every reason we have examined the facts with anxiety to give the full weight to any argument by which the plaintiff’s pious wishes might be carried out.” But the Court agreed with the Kansas district court’s decision that Conley did not have standing to bring the case because the Wyandots had signed a treaty in 1855 agreeing to dissolve their tribe and cede their lands in exchange for becoming U.S. citizens. (Many Wyandots moved to Oklahoma and established the federally recognized Wyandotte Nation. The Conleys had opted to stay in Kansas City and persisted in calling themselves Wyandots even though the U.S. government legally counted them as citizens.) That the 1855 treaty had specifically omitted the burial ground from the sale and “permanently reserved” it for use by the Wyandot people did not sway the Court. Justice Holmes held that this did not legally oblige the federal government to protect the cemetery.

Conley may have lost the legal battle but she won the public relations war. Senator Charles Curtis (R-KS), a member of the Kaw Nation persuaded Congress to repeal the sale authorization in 1913. Until her death in 1947, however, Conley continued to fight off developers as the cemetery, in the heart of downtown Kansas City, was eyed as prime real estate. (By then, the Conley sisters lived together in a house offsite, U.S. marshals having razed their shack.)The sacred burial ground—where some 800 are now interred, including the Conley sisters—was not fully protected until 2017 when it became a National Historic Landmark.

Lyda B. Conley is remembered as a Supreme Court “first”—the first woman of Native American descent to argue a case in the Supreme Court—115 years ago. (She was officially admitted to the Supreme Court bar in 1915, on motion of John W. Davis, the leading advocate of his generation.) Conley should also be hailed as a visionary who, on her own, formulated compelling legal and moral arguments that the burying grounds of Native Americans were entitled to federal protection.