Wilkinson’s parents were free Blacks who moved to D.C. from Virginia in 1831. He attended school from ages 9 to 11 and then worked as a bricklayer. His father, a clerk at the Library of Congress, presumably helped him get hired to work in the Law Library. But he almost didn’t have much of a career there. Four years after his hiring, the newly-appointed Librarian of Congress, John Gould Stephenson, dismissed Wilkinson, saying “it had been decided to employ no colored help.” Both Taney and Senator Reverdy Johnson, a member of the Joint Committee on the Library, intervened to have him reinstated after two months because his knowledge of the collection had already made him indispensable. Reluctant to return, Wilkinson was assured by Taney that he would not be discharged again. (When admirers later put forth his name to be promoted to Law Librarian, he was not selected–presumably on account of his race.)

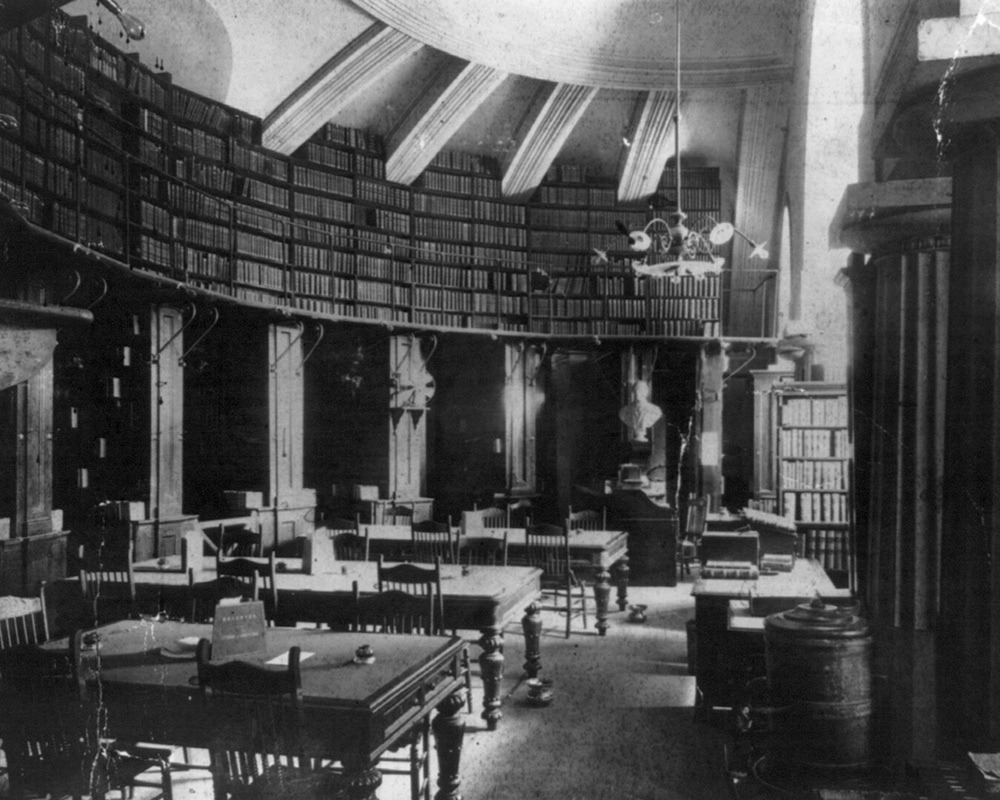

Wilkinson served as the only assistant to the first Law Librarian of Congress, Charles Henry Wharton Meehan for 15 years and then went on to serve under four more Law Librarians. Despite his lack of education, he relished the opportunity to become familiar with all the titles and locations of materials as well as to read up on legal subjects. The rules of the Law Library, set down by the chief justice, permitted not just the justices and members of Congress but also “gentlemen of the bar having a case on the docket” to sign out up to three books from the collection. (A special collection of major texts and court decisions was reserved for the exclusive use of the justices.) Wilkinson was an invaluable resource for oral advocates preparing cases for argument and he maintained contacts with lawyers across the country. His memory was prodigious and legendary.

In 1885, after 28 years on the job, Wilkinson was described by a visiting journalist as “a remarkable librarian” who “draws out the required works from the shelves” with the “precision of a Swiss bell-ringer.” His eyewitness report captures Wilkinson’s astonishing expertise:

No abbreviations of the law reporter stagger him. He refers to no dictionary to discover the meaning of initials or condensed names used, but promptly goes to the proper alcove, and unerringly brings forth the desired report, whether it be one of a musty British series or some earlier State collection of opinions whose editor sought to emblazen his own name upon it rather than employ the modern convenience of consecutive numbers. It is this perfect familiarity with the library which impresses Mr. Wilkinson upon the visitor. The pages of the Supreme Court Justices are momentarily coming down with requisitions for authorities that may range from the ancient Breton laws, French causes celebres, or reports of the Court de Cassation, to the whole domain of American decisions… But what is more remarkable as a feat of memorizing is the accuracy of his recollection of cases. He has no need of recourse to digests to locate the leading cases in our jurisprudence. The library has grown during Mr. Wilkinson’s incumbency from 15,000 to 63,000 volumes, but he has kept pace with it.

By the time the Law Library reached 80,000 volumes in 1892, Congress finally appropriated money to catalog it. Wilkinson nonetheless remained a valuable library stalwart until the day of his death in 1912. He holds the record for longevity—55 years—at the Law Library of Congress. At his funeral, Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam, said: “To an exact memory of the books, he added an exact memory of persons, and his prompt, simple, and respectful service made so favorable an impression upon Members of Congress, the bar, and the Justices of the Supreme Court.”

Wilkinson had an active life in his community. He married Rachel Ann Bell in 1868 and they had four children. He was one of a small number of Black members of the District of Columbia School Board of Trustees and a leader in the city’s Emancipation Day celebrations. He was a positive force in a wide variety of African-American fraternal organizations. “[He] belonged to that rare set of colored leaders in this city, who accomplished great things without notice and the blare of trumpets—things affecting the education needs of the race as well as their civil and political rights. . . .” said an admiring obituary in the Washington Bee.

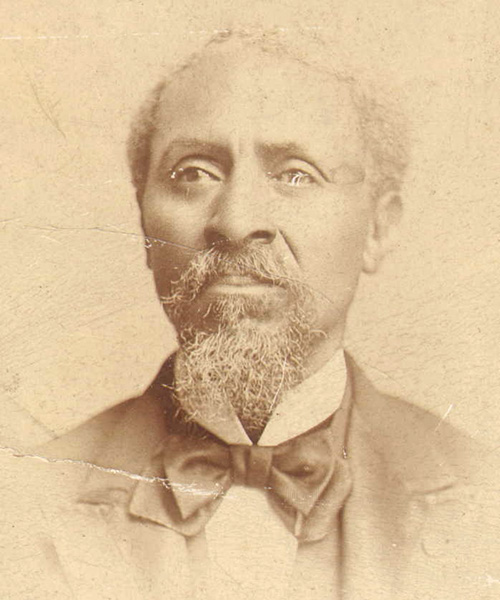

Wilkinson was an invaluable resource for Supreme Court justices and for oral advocates preparing cases for argument. His memory was prodigious and legendary. Credit: ancestry.com

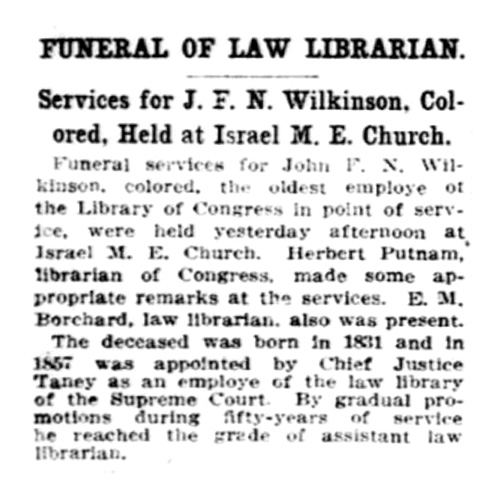

Evening Star, October 10, 1912.