Over the summer, we have been reviewing Chief Justice Warren E. Burger’s personal papers, which are housed at William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, as we prepare to start writing his official biography. One of our favorite finds in the personal papers are the little vignettes that the Chief Justice recorded about his personal and professional life. It’s remarkable to have a Justice’s own memories preserved for a project such as ours, and it affords students of the Court the rare opportunity to hear from the Chief Justice himself. In the short essay below, Chief Justice Burger explains why he discouraged the tradition of the justices reading opinions from the bench and stopped requiring lawyers to physically appear before the Court in order to be admitted to the Supreme Court bar.

* * *

I had announced before the first opinions came down in the Fall of 1969 that I thought the reading of opinions or even lengthy summaries was an anomaly in the modern time and totally useless. It consumed an enormous number of hours of the Justices in the course of a year (I had estimated at least 300 hours!) for it was not uncommon for the court to spend the entire morning session and even going into the afternoon with the combination of reading of the opinions and admitting lawyers.

The rule had been, for one hundred and eighty years, that a lawyer must be present himself in person in the courtroom to be admitted. This was actually an absurdity and a carry over from earlier times. It put a great and unnecessary burden on lawyers to make a trip to Washington in order to qualify even to sign a motion or petition for certiorari or a jurisdictional statement or any other pleading. No other court in the United States, and so far as I know no other court in the common law world, had any such absurd requirement. The change was made in the Spring of 1970, at least as to the admission of lawyers, and a compromise was reached that we would permit lawyers to appear “in the flesh” if they wished to but that they could also be admitted on papers. I suppose one factor that influenced my thinking was that I had largely written the briefs in the case of SRA v. State of Minnesota . . . [S.R.A., Inc. v. Minnesota, 327 U.S. 558 (1946)] but could not sign the briefs and my name does not appear in the records of the Court as participating because I was then not admitted (Since it was a ”loser” I should not complain). Lawyers could ill afford a trip to Washington for the sole purpose of getting admitted in order later to sign a petition or brief. The alternative for many of them was to pay a Washington lawyer $300-500 to put his name on the brief until the lawyer who was local counsel could appear in the courtroom on the very day that he was to argue the case, if it was argued.

This change was accomplished in the Spring of 1970 over the somewhat reluctant, even mildly grumbling objections of Hugo Black and John Harlan. They thought we should preserve the “great tradition” both on opinions and admissions. On the matter of opinions I have steadily adhered to what I had announced and I think the sole exception was that on the urging of the other members of the Court I gave what the press said was a 17 minute summary of the opinion of the Court in the Nixon tapes case.

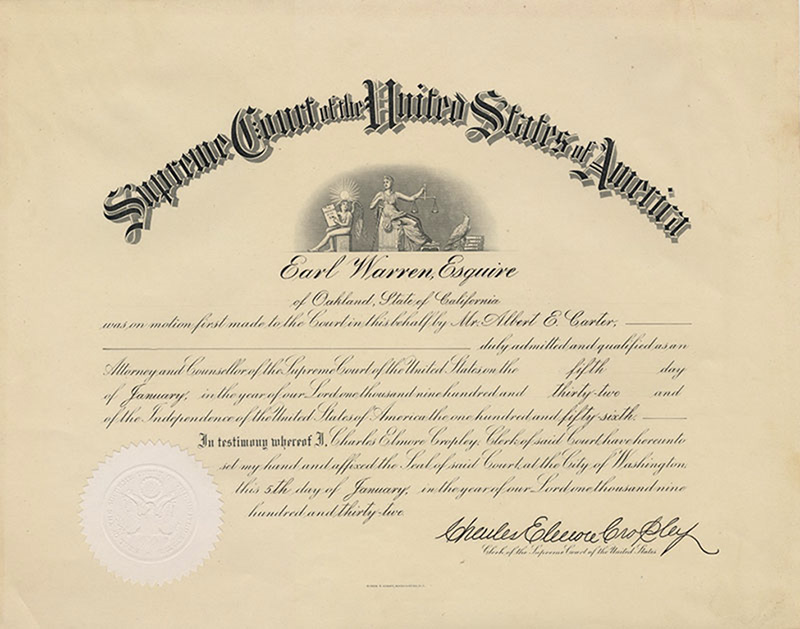

The Supreme Court Bar certificate of Earl Warren from 1932, issued in the era when attorneys were required to be admitted in person. Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States.