When the Supreme Court reviewed the Standard Oil antitrust case in 1910, it affirmed the order but altered the law. Congress, said Chief Justice Edward Douglass White, only meant the law to punish “unreasonable” restraint of trade. White’s “rule of reason” became a rule of law.

In 1914 the Supreme Court announced that if federal officers seize things illegally, federal judges must not admit such things in evidence in their courtrooms. But that decision did not bind state courts. Until 1961 the Court left states free to admit such evidence if they chose.

In January 1916, President Woodrow Wilson nominated Louis D. Brandeis for Associate Justice. Brandeis had successfully argued Muller v. Oregon before the Supreme Court in 1908, but the New York Times thought the Court no place for “a striver after changes.” William Howard Taft and Joseph H. Choate called him “not a fit person” for the bench. The Senate wrangled for almost five months before confirming him.

Of all challenges to reform, child labor was the most poignant; “a subject for the combined intelligence and massed morality of American people to handle,” said Senator Albert J. Beveridge. In 1916 Congress passed a law to keep goods made by child labor out of interstate commerce.

As a result, John Dagenhart, less than 14, would lose his job in a textile mill in Charlotte, North Carolina. His brother, Reuben, not yet 16, would lose 12 hours of piecework a week.

Their father asked the federal district court to enjoin the factory from obeying the law and United States Attorney William C. Hammer from enforcing it. As “a man of small means,” with a large family, he complained, he needed the boys’ pay for their “comfortable support and maintenance.” Their work was “altogether in the production of manufactured goods” and had “nothing whatsoever” to do with commerce.

When the district judge granted the injunctions, the U.S. attorney appealed to the Supreme Court. Five Justices thought that in enacting the Child Labor Law Congress had usurped the powers of the states; such laws might destroy the federal system.

Legislation can begin where an evil begins, retorted Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, dissenting. If Congress chooses to prohibit trade in “the product of ruined lives,” the Court should not outlaw its choice. He added: “I should have thought that if we were to introduce our own moral conceptions where in my opinion they do not belong, this was preeminently a case for upholding the exercise of all its powers by the United States.”

Three Justices joined Holmes’s dissent. So did Congress; it promptly set high taxes on products of child labor.

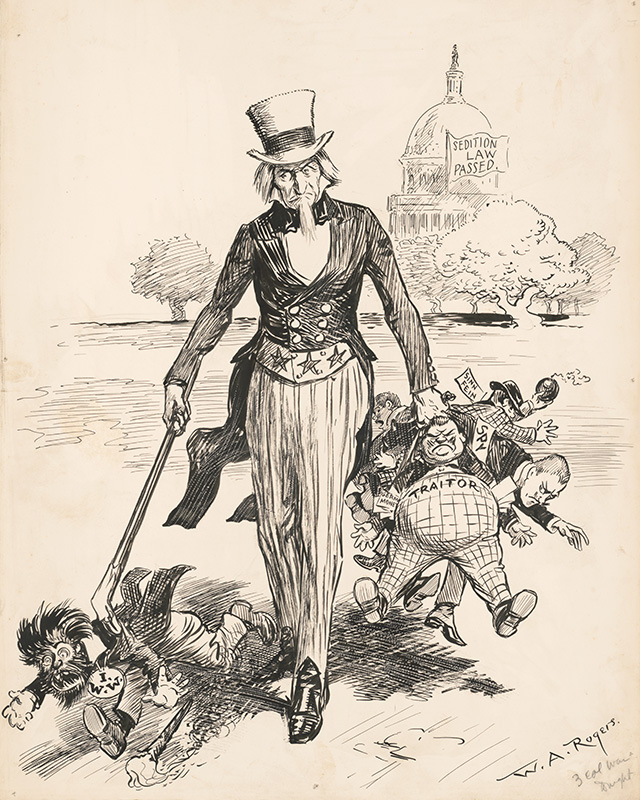

Two months after Congress declared war on Germany in April 1917, it passed an Espionage Act that punished attempts to obstruct enlistment and discipline in the armed forces. In 1918 it passed a Sedition Act so broadly worded that almost any critical comment on the war or government might incur a fine of $10,000, or 20 years in prison, or both.

Under the 1917 law, government attorneys filed almost 2,000 prosecutions, among them United States v. “The Spirit of ’76.” Only a handful of these cases reached the Supreme Court. Only after the Armistice did the Justices hear a case challenging the law by the First Amendment guarantee of free speech.

Charles T. Schenck and other members of the Socialist Party in Philadelphia were convicted of conspiring to mail circulars to drafted men. In forbidding slavery, these leaflets said, the Thirteenth Amendment forbade the draft.

For a unanimous Court, Holmes wrote that “in many places and in ordinary times” the Socialists would be within their constitutional rights. But the Bill of Rights does not protect words creating a “clear and present danger” of “evils that Congress has a right to prevent.” Schenck was sentenced to six months in jail.

But Holmes and Brandeis dissented when the 1918 Sedition Act, and leaflets in English and Yiddish, came before them. Flung from a factory window to the New York streets on August 23, 1918, these papers summoned “the workers of the world” to defend the Russian Revolution against despots. “P.S.,” said some, “We hate and despise German militarism more than do your hypocritical tyrants.” By a seven-to-two majority, the Court upheld criminal convictions under the Act.

In his elegant dissent, Holmes remarked, “Congress certainly cannot forbid all effort to change the mind of the country.” He saw no national danger in the “usual tall talk” of “these poor and puny anonymities.” But he saw danger in persecution of opinions, for “time has upset many fighting faiths” and the national good requires “free trade in ideas.” To reach the truth, people must weigh many opinions. “That at any rate is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all of life is an experiment,” Justice Holmes concluded.