For Chase’s successor, the Senate confirmed President Grant’s nomination of Morrison R. Waite in 1874. Thoroughly respectable, this 57-year-old attorney from Ohio lacked the nationwide fame of Jay or Marshall or Taney or Chase.

“I am getting the hang of the barn a little,” Waite wrote modestly after a week in Washington. By 1877, when he gave the Court’s decision in the Granger cases, he had gotten it thoroughly.

Corn in the woodbox fed the political prairie fire of the Granger movement. Railroads were charging so much to ship grain that farmers burned it for fuel instead of sending it for sale. Joining the Grange, or Patrons of Husbandry, farmers took their wrongs to their legislatures; four states limited freight rates by law.

Illinois farmers had unexpected allies, merchants from the Chicago Board of Trade, so disgusted at sharp practices in the grain storage business that they were willing to fight for state regulation. When Illinois law set standards for warehousing, the firm of Munn & Scott was in trouble.

With huge grain elevators in Chicago, Ira Y. Munn and George L. Scott had piled up a fortune, a name for crooked dealings, a lot of enemies, and bankruptcy.

Used to charging what the traffic would bear, the railroads found state regulation unbearable; they took their wrongs to court.

When state and federal judges upheld the “Granger laws,” railroad attorneys steamed hopefully to the Supreme Court, quoting the Fourteenth Amendment on due process of law, the contract clause, and the interstate commerce clause of the Constitution. With them went lawyers for the ruined Ira Munn, still fighting a $100 fine for illegal storage rates. If these laws stood, they argued, private property would be wrecked.

Seven Justices found all these laws valid. Like Taney, they thought community rights as sacred as corporation rights. “For us the question is one of power,” said Waite; when private property affects the community, the public has constitutional power to protect its interest by law, for the common good. Firms like Munn & Scott had virtual monopolies on grain—so Illinois could exercise its power to regulate them.

Waite assigned a modest role to the courts; they must assume that a legislature knows the facts, and they must accept the legislature as “the exclusive judge” of when to pass regulatory laws and what to say in them.

The railroads contended that only Congress could regulate their trade; Waite ruled that until Congress did, the states were free to act within their own borders.

The New York Herald said: “either the people would govern the railroads, or the railroads would govern the people. The Supreme Court has come to the rescue. . . .”

But Justice Field, dissenting, called the decisions “subversive of the rights of private property.” And his dissent would become the majority opinion in later decisions.

Under the Civil Rights Act of 1875, designed to prevent discrimination in public places, Negro citizens brought cases before the Court, protesting their exclusion from a hotel dining room in Topeka, an opera house in New York, the dress circle of a San Francisco theater, the ladies’ car on a train. In 1883, eight Justices held the act unconstitutional. The Fourteenth Amendment, they said, only gave Congress power over state action; if private citizens discriminated among one another, Congress could do nothing about it. John Marshall Harlan of Kentucky, the Court’s only southerner, wrote a fighting 36-page dissent.

Although discrimination in the train cars remained an issue to be addressed, the railroads, which had rushed beyond state borders and laws, faced new legislation when Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act in 1887.

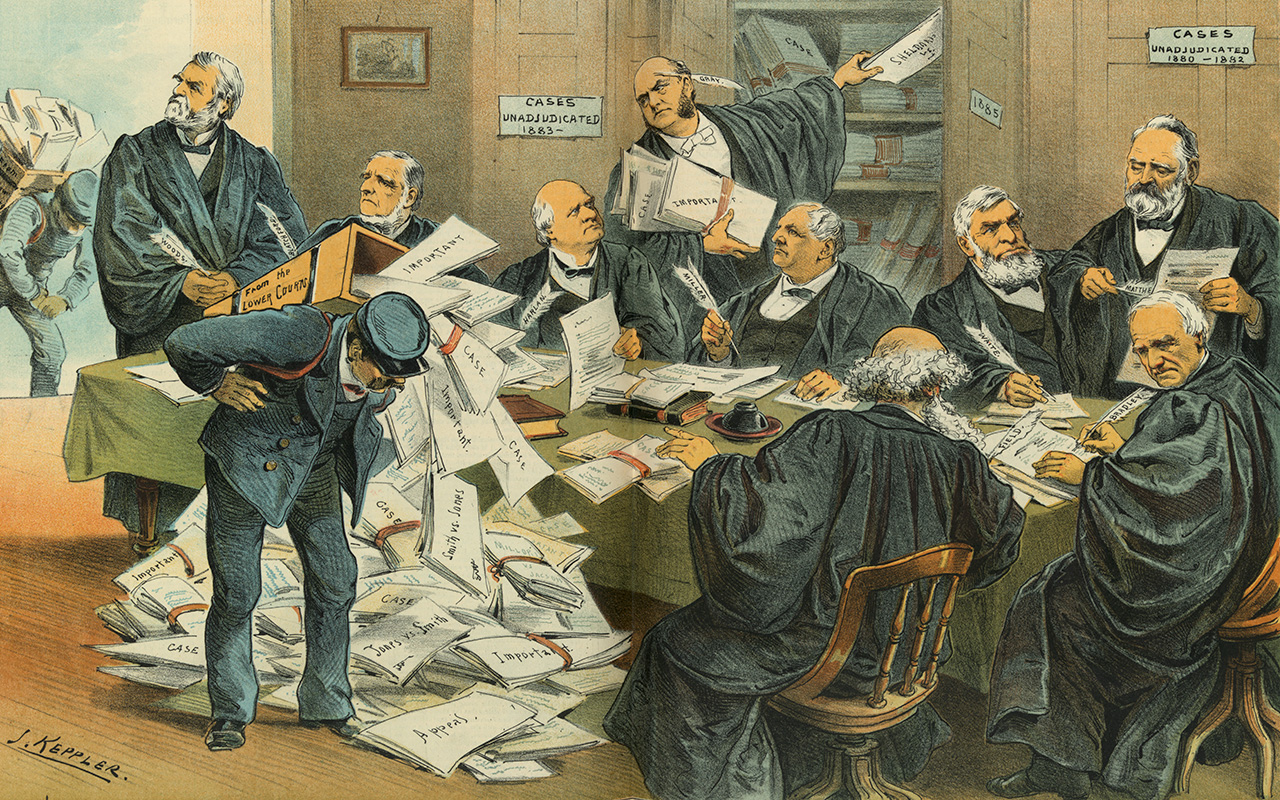

“Justice delayed is justice denied”—the Supreme Court saw this in 1887, when it was almost four years behind in its work. Appealing to the public, Chief Justice Waite sought “relief for the people against the tedious and oppressive delays” of federal justice. Waite died the following year, in 1888.