About Marshall’s successor, a New York journal sputtered: “The pure ermine of the Supreme Court is sullied by the appointment of that political hack, Roger B. Taney.” Daniel Webster confided, “Judge Story . . . thinks the Supreme Court is gone and I think so too.” The Senate debated the nomination for almost three months.

Born in Maryland in 1777, Taney attended Dickinson College, read law, and plunged into Federalist politics. While other lawyers took pride in oratory, he spoke simply in low tones that convinced juries.

Invoking freedom of speech, Taney won acquittal in 1819 for a Methodist preacher whose sermon on national sins provoked the charge of trying to stir up slave rebellion.

Suspicious of the Bank of the United States, Taney campaigned for Andrew Jackson. In 1831 President Jackson wrote, “I have appointed Mr. Tauney atto. Genl.” (His spelling gives the right pronunciation.) Taney supplied legal weapons in Jackson’s war with the Bank, when passion ran so high that Vice President Martin Van Buren wore pistols to preside in the Senate.

Presiding over the Supreme Court for the first time, in January 1837, Taney wore plain democratic trousers, not knee breeches, under his robe. The Court was entering a new era. A law passed in March added two new judicial circuits in the southwest and two Associates Justices. The Court became unmistakably Jacksonian; conservatives dreaded what it might do to property.

But property survived. Its rights were “sacredly guarded,” Taney wrote in the Charles River Bridge case, but “we must not forget that the community also have rights, and that the happiness and well being of every citizen depends on their faithful preservation.” He interpreted corporation charters more strictly, state powers more generously, than Marshall had.

Meanwhile, a new agitation over human rights was growing. If it went on, wrote a Georgia planter, “we will be compelled to arm our Militia and shoot down our property in the field . . . tell the agitators we had rather fight them than our own negroes, and that we will do it too. . . .”

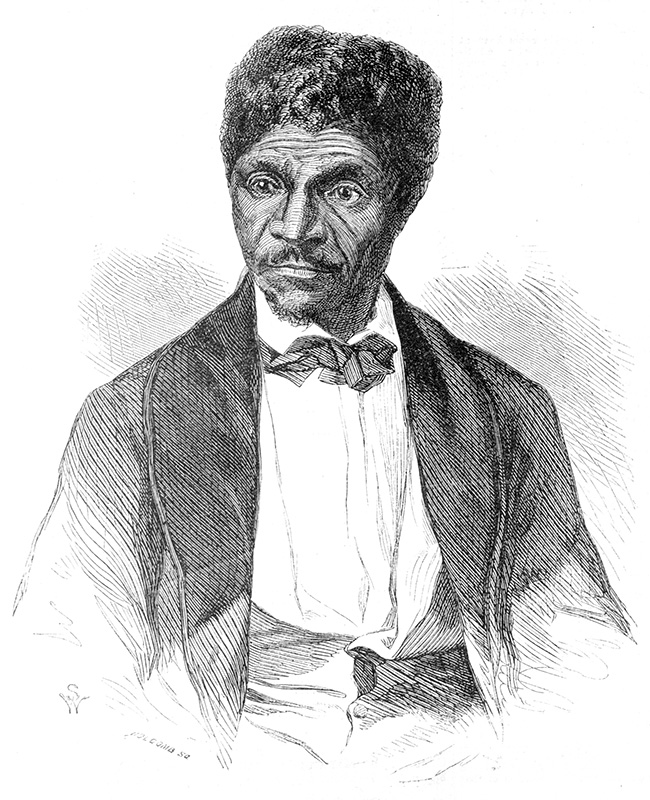

In 1846 the United States and Mexico went to war. A suit filed in a Missouri court by a Negro named Dred Scott went unnoticed. Twelve years earlier, John Emerson, an Army surgeon, had taken his slave Scott from Missouri to Illinois, where the Northwest Ordinance and state law forbade slavery. Then he had taken Scott to Fort Snelling, a frontier Army post in territory where the Missouri Compromise banned slavery forever. In 1838 he had taken Scott back to Missouri. Emerson died, and Scott sued the widow, claiming that this sojourn on free soil had made him a free man. In 1850 the Missouri court declared him free.

Mrs. Emerson appealed. The state’s highest court ruled in 1852 that, free or not on free soil, Scott became a slave under state law when he went back to St. Louis.

Scott’s was becoming a test case. To get it into a federal court—because federal courts have jurisdiction in suits between citizens of different states—title to Scott passed to Mrs. Emerson’s brother, John F. A. Sanford of New York (misspelled “Sandford” in the records).

Claiming Missouri citizenship, Scott sued Sanford for his freedom in the federal court in St. Louis. Sanford’s lawyers argued that Scott could not be a citizen because he was a slave and a Negro. The court ruled against Scott on May 15, 1854.

Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act two weeks later, opening areas of the West to slavery where it had been banned by the Missouri Compromise. Furious northerners burned its author, Stephen A. Douglas, in effigy. On July 4, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison publicly burned a copy of the Constitution, crying, “So perish all compromises with tyranny.”

Fighting broke out in Kansas and made the expansion of slavery the issue in the 1856 Presidential campaign, won by James Buchanan. The Supreme Court heard argument in Dred Scott. v. Sandford in February 1856, reached the end of its term, then heard argument again in December.

By then the whole country had heard of Dred Scott. “The Court, in trying this case, is itself on trial,” said the New York Courier.

In February 1857, a majority of the Justices agreed to follow precedent and say that the ruling of the highest state court was final—that Scott was a slave under state law. Such a narrow finding would leave unresolved two dangerously controversial issues: Whether or not a free Negro might be a citizen of the United States, and whether or not the 1820 Missouri Compromise was constitutional.

When it was learned that two dissenting Justices planned to argue that Congress in fact had the power to regulate slavery in the territories, that under the Missouri Compromise Scott was a free man and a citizen, the majority decided to enlarge the scope of the decision and deny the power of Congress. Some members hoped the Court’s opinion would resolve the question, win acceptance, and possibly save the Union.

Newly elected President James Buchanan may have shared that hope; in his Inaugural Address on March 4, he promised that “in common with all good citizens” he would “cheerfully submit” to the Court’s decision.

Two days later the Justices began to deliver eight separate opinions. The majority ruled that Scott was still a slave. Three, including Taney, said no Negro, even if free, could hold citizenship in the United States.

And for the first time since 1803, the Court held an Act of Congress null and void. Under the Constitution, it announced, Congress had no power to limit the expansion of slavery by law, as the Missouri Compromise of 1820 had done.

Hopes that the decision would temper the confrontation were shattered by attacks on the Court from the abolitionist press and antislavery leaders—attacks that have never been surpassed in bitterness. Almost unnoticed, Scott’s owner set him free. Before the case was decided, Sandford had gone insane; before the slavery question was settled, more than 600,000 Americans would lose their lives in civil war.

“Have we ever had any peace on this slavery question?” asked Abraham Lincoln. The Illinois crowd yelled “No!” It was 1858; Lincoln was challenging Stephen A. Douglas for a Senate seat — challenging the Supreme Court’s ruling on slavery.

Douglas defended the decision in Dred Scott’s case as the pronouncement of “the highest tribunal on earth,” in spite of his own objections to it. “From that decision there is no appeal this side of Heaven,” he cried.

One decision settles one case, retorted Lincoln; it does not even settle the law, still less the future of the country.

Douglas won the Senate seat; in 1860 he lost the race for the Presidency, and the Republicans came to power with Lincoln.

Chief Justice Taney administered the oath of office to Lincoln on March 4, 1861, and heard him disclaim “any assault upon the Court.” But Lincoln warned solemnly: “if the policy of the Government, upon vital questions affecting the whole people, is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court, the instant they are made, in ordinary litigation . . . the people will have ceased to be their own rulers. . . .”

That day the first banner of the Confederate States of America flew over the statehouse at Montgomery, Alabama.

Secession divided the Supreme Court. Justice John A. Campbell, who thought disunion wrong, resigned and went sadly home to Alabama. Justice James Moore Wayne of Georgia, last survivor of Marshall’s Court, remained; until his death in 1867, he voted to sustain all the war measures the Court passed judgment on.

In Maryland, part of Taney’s circuit, many favored the Union, some the South. Washington’s only railroad to the north ran through Baltimore, where an angry crowd mobbed troops hurrying to defend the capital. Lincoln told the Army to suspend the writ of habeas corpus and establish martial rule, if necessary, to keep Maryland safe.

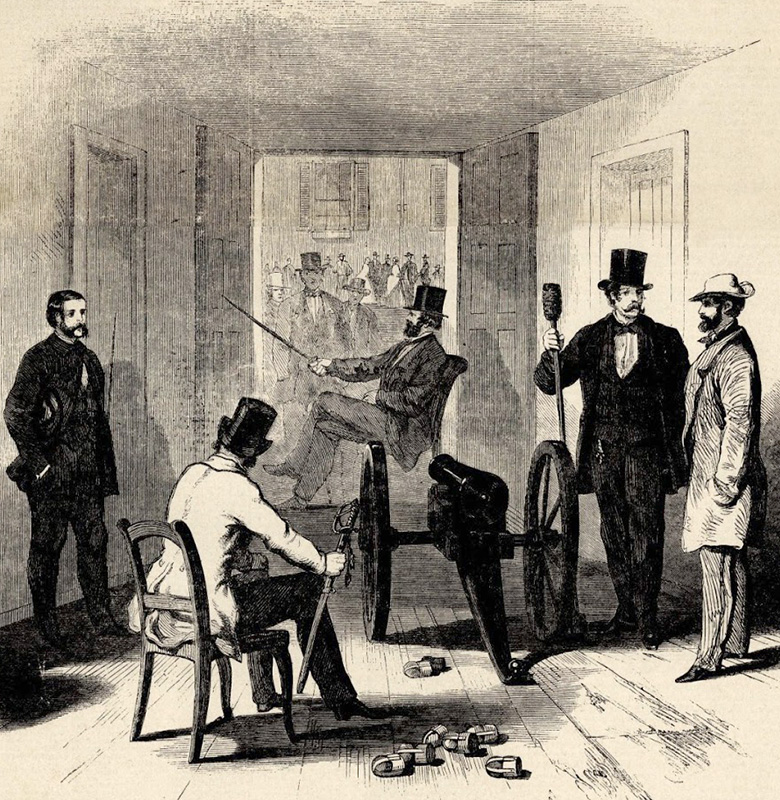

The military jailed citizens on mere suspicion; troops arrested John Merryman for taking part in the Baltimore riot and blowing up railroad bridges. Locked up in Fort McHenry, he applied for a writ of habeas corpus—a court order for proof that a prisoner is lawfully confined.

Only in “Rebellion or Invasion” when “the public safety may require it” may the privilege of habeas corpus be suspended, says the Constitution.

Hurrying to Baltimore, Chief Justice Taney issued a writ to Gen. George Cadwalader: Bring Merryman to court and explain his arrest. The general sent a letter—he had to consult the President. Taney ordered a marshal to seize the general, but a sentry barred the marshal from Fort McHenry. The Chief Justice challenged the President’s right to take legislative and judicial power, calling on him to uphold the law and the courts.

Lincoln did not reply; Congress upheld him. But when the emergency had passed, the government quietly brought Merryman’s case to a federal court; later still, it quietly let him go free.

Resignation and death left three seats vacant at the Supreme Court. Lincoln appointed Noah H. Swayne of Ohio, Samuel F. Miller of Iowa, and his old friend from Illinois, David Davis. But no one knew what the Court would do when it heard the Prize Cases in 1863.

Before calling Congress into special session, Lincoln had authorized martial rule in Maryland, called for volunteers, pledged government credit for huge sums, and proclaimed a blockade of southern ports. To meet the crisis of war, the President swept into the realm of legislative power like an invading general. A legal battle over four merchant ships seized under Lincoln’s blockade orders tested his actions before the Supreme Court.

The owners brought suit for the vessels and cargo, arguing that war alone warrants a blockade and only Congress may declare war; they denied that Lincoln’s emergency powers had any reality in constitutional law.

If the Court upheld the blockade as a legal war measure, England and France might recognize the Confederacy; if it did not, the government would have to pay huge damages for captured ships, and other war measures would be in question. Either decision would endanger the Union.

Justice Robert C. Grier spoke for himself, Wayne, and Lincoln’s three appointees: The President had to meet the war as “it presented itself, without waiting for Congress to baptize it with a name”; and rebellion did not make the South a sovereign nation. Four dissenters said the conflict was the President’s “personal war” until Congress recognized the insurrection on July 13, 1861. But the prairie lawyer had won his case.

Chief Justice Taney died, aged 87, in October 1864. Lincoln’s Attorney General Edward Bates wrote that his “great error” in the Dred Scott case should not forever “tarnish his otherwise well earned fame.” And not long after Taney’s death, victory for the Union brought vindication of his defiant stand for the rule of law.