Legal questions often display remarkable resistance to permanent resolution, and new facts constantly invite reexamination of old law. So it is not surprising that the Rehnquist Court has encountered many of the same issues faced by its predecessors. If often occupied more with refining the law than with establishing broad new principles, the current Court continues to decide issues relating to, for example, the death penalty, abortion, school desegregation, freedom of religion, and civil rights. Yet fundamental changes in American society have frequently required the Rehnquist Court to venture into relatively uncharted legal terrain as well. For instance, the Court is regularly called upon to decide whether, and to what extent, the nation’s civil rights laws protect not just groups defined by race, ethnicity, or religion, but by gender, sexual orientation and physical ability as well. At the same time, new and rapidly evolving technologies have forced the Court to consider when medical care must give way to a patient’s right to die, whether speech on the internet should be as “free” as it is in more traditional media, and when law enforcement’s use of new investigative technologies becomes an “unreasonable” invasion of constitutional rights.

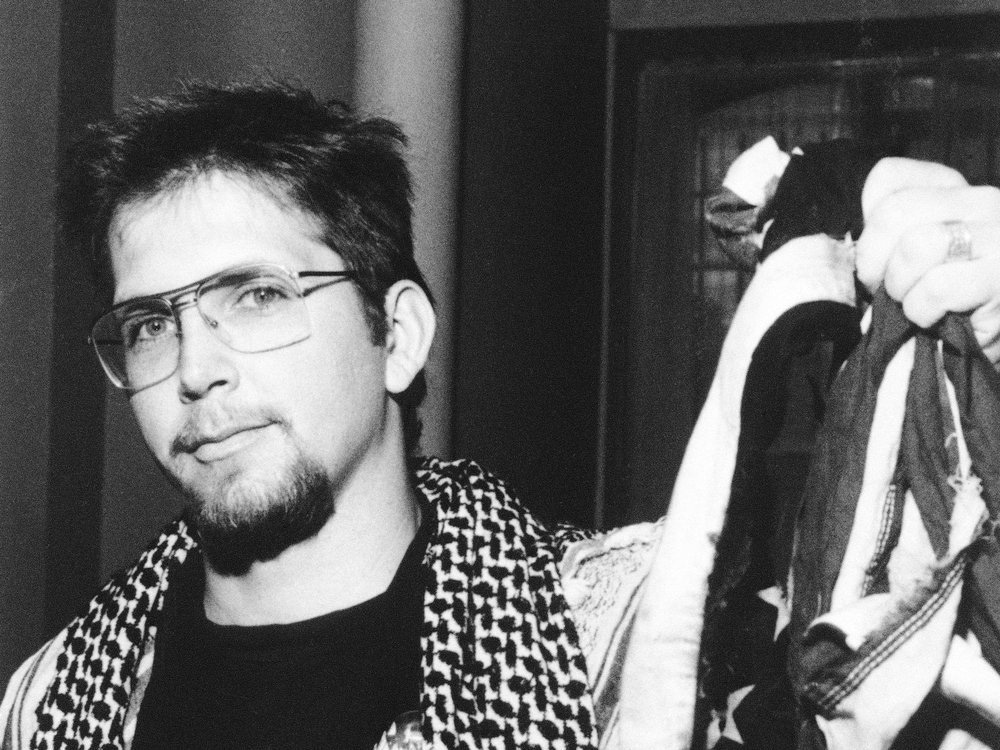

Considering more familiar legal terrain first, the Rehnquist Court has issued a number of important First Amendment decisions involving both speech and religion. For instance, in the 1989 flag-burning case, Texas v. Johnson, the Court confirmed that the First Amendment protects even the most unpopular forms of speech, including speech viscerally distasteful to many of the Justices themselves. Arguably, however, the Rehnquist Court’s most important free-speech cases have involved commercial rather than political or other non-commercial speech. Although long considered of little social value, the Court’s recent decisions reflect a growing respect for the importance of commercial speech. As a result, the Court now evaluates restrictions on commercial speech by increasingly exacting standards. Accordingly, the Court has struck down a city ordinance used to ban the placement of certain newsracks on public property where there were less burdensome alternatives for achieving the city’s aesthetic and safety goals, and where the city discriminated between newsracks distributing advertising circulars on the one hand, and regular newspapers on the other. In another case, the Court rejected a state law prohibiting liquor sellers from advertising the price of alcoholic beverages as an unconstitutional restriction on truthful, non-misleading advertising. Separately, the Court struck down a federal law prohibiting brewers from displaying alcohol content on beer labels.

Other First Amendment cases have illustrated the potential tension between its protection of free speech on the one hand, and freedom of religion on the other. In one case, for instance, fear of unconstitutionally endorsing religion caused the University of Virginia to deny funding to student-run religious publications on equal terms with other student publications. When the students sued, the Court held that the University had violated their right to free speech.

At the same time, the Court itself has faced the difficult task of maintaining the often elusive balance between government not endorsing religion on the one hand, but not penalizing it on the other. Thus, the Court has held that a State may not create a school district for the particular benefit of a specific religious sect’s disabled children. Neither may a state deny certain generally available public benefits to students merely because they attend a private, religious school rather than a public or other secular school. Ultimately, however, the Rehnquist Court’s religious-freedom jurisprudence might best be viewed as an ongoing effort to establish usable criteria for determining when government action crosses the constitutional line in one direction or the other. For example, in County of Allegheny v. ACLU (1989) a fractured Court held that a crèche standing alone inside a county courthouse impermissibly endorses religion, but a menorah displayed next to a Christmas tree on the lawn outside does not.

A similar effort is discernable in the Court’s recent attempts to define when government regulations that affect the use of private property become a constitutional “taking” of that property. As with so many issues, the primary difficulty in establishing fixed and usable criteria lies in the need to establish the appropriate balance between important but competing interests — here the property owner’s interest in unrestricted use of private property, and the government’s interest in controlling how such use affects the greater, common good.

In 1987, the Court made it clear that property owners are entitled to compensation even if a regulation “takes” their property only temporarily. But subsequent decisions have yet to clarify exactly when a “regulatory taking” occurs, although some guiding principles have emerged. Thus, a compensable taking occurs when regulations impose burdens on private property that are unrelated to the public interest those regulations are intended to serve. For instance, conditioning a building permit for beachfront property on an easement allowing people already on the beach to cross from one side of the property to the other would not substantially further the State’s claimed interest in providing adequate public access to reach the beach in the first place. Moreover, the burdens of regulatory restrictions on private property must be not only related to, but also reasonably proportionate to, the public interests they are purported to serve. Finally, regardless of relationship and proportion, a regulatory burden is a taking if it deprives owners of all economically beneficial use of their property (unless the regulation merely prohibits activities traditionally considered to be a public nuisance or noxious use). That will not occur, however, if part of the property can be developed despite the regulation, even if the remainder cannot.

More definite rules have emerged from recent decisions regarding the Constitution’s equal-protection guarantees. It has long been clear, of course, that any government law or action that discriminates against certain classes of people (e.g., racial minorities) is subject to the strictest judicial scrutiny. In judicial shorthand, such discrimination is valid only if it is very narrowly tailored to fulfill a compelling government interest. But a series of decisions by the Rehnquist Court are important for applying the same exacting standards to the flip side of the discrimination coin. Thus, the Court has frequently invalidated even so-called affirmative discrimination — laws and other actions intended to benefit the victims of past discrimination — where the government has not been able to show both narrow tailoring and a compelling interest. In 1989, for example, the Court struck down a Richmond ordinance that set aside a fixed percentage of all city-contract work for minority businesses, because the city had not shown that the set-aside remedied specifically identifiable effects of past discrimination on a specifically identifiable class of minorities. The Court has applied the same rule at the federal level: in Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena (1995) it rejected the presumption in a federal contracting program that all minority-owned businesses are socially and/or economically disadvantaged as a result of past discrimination. A series of important voting-rights decisions have similarly rejected attempts to remedy past discrimination by drawing the boundaries of congressional districts in an unnatural way to ensure that members of racial minorities will be elected to Congress.

In addition to policing the relationship between government and the people, the Rehnquist Court has issued a number of important decisions helping to define, and perhaps even redefine, the relationship between the federal government and the States. The Court’s decisions in this important area of national life essentially break down into two important categories. One line of decisions has substantially narrowed Congress’ authority to legislate in the name of regulating interstate commerce. From the late 1930s until relatively recently, the Court’s formerly narrow view of Congressional authority under Article 1, Section 8’s Commerce Clause expanded until that authority appeared virtually unlimited. Particularly since 1995, however, more recent decisions have marked a sharp reversal in that trend. Accordingly, it is not enough that the activity being regulated somehow affects interstate commerce, no matter how minor the effect or how remote the connection. At a minimum, the object or activity being regulated must have a “substantial” and demonstrable effect on interstate commerce, and there is some indication that even the activity itself may have to be fundamentally “economic” in nature.

For example, the fact that violence against women may substantially deter women from engaging in activities affecting interstate commerce was not enough to save a 1994 law making all violent acts against women federal crimes. Despite its good intentions, the Court concluded, the law impermissibly invaded an area of regulation constitutionally left to the States. An earlier law banning the possession of firearms in or around schools, where it had not been shown that such possession had any meaningful effect on interstate commerce, met a similar fate. Importantly, other cases make clear that even when Congress’ power to regulate is unquestioned, it has no power to compel unwilling state agencies and officials to enforce federal regulatory regimes. For example, while Congress may have the power to enact federal laws regulating the sale of handguns, it cannot compel State law-enforcement personnel to implement or administer the programs necessary to do so.

Another line of recent decisions has begun to establish important limits on the power of Congress to abrogate the State’s sovereign immunity under the Eleventh Amendment. In most instances, private citizens have no right to sue a State for money damages unless the State consents to be sued. Although Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment gives Congress the power to pass laws subjecting the States to private suits, it may only do so as a means of enforcing rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment itself. Thus, while Congress might make a State monetarily liable to a person against whom it has discriminated on the basis of race in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, it has no similar power where a State discriminates on the basis of age without triggering the Fourteenth Amendment’s prohibitions. Moreover, the power to regulate activity within a State does not automatically carry the power to abrogate the State’s immunity from private suit. For example, while the Commerce Clause may give Congress the power to regulate Indian gaming within the States, that does not mean that Congress can authorize Indian tribes to sue a State that fails to negotiate a gaming permit in good faith.

If such decisions revolve around facts and circumstances similar to those that have faced the Court since the founding of the Republic, other cases decided by the Rehnquist Court have been prompted by technological innovations that its predecessors may never have imagined. In the 1990 case Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health, for instance, the continuing march of medical progress forced the Court to establish a difficult balance between a patient’s right to die and the State’s interest in protecting human life. Often discussed in terms of its economic implications, the internet’s social ramifications became a topic of Supreme Court consideration in Reno v. ACLU (1997) when it rejected Congress’ first attempt to regulate speech in cyberspace. And in 2001, the Court had to decide whether police use of a thermal imager positioned outside a private home, to detect heat lamps being used to grow marijuana inside, violated the homeowner’s reasonable expectation of privacy. The Court held that it did in Kyllo v. United States.

Political developments, too, have required the Court to decide some particularly novel legal issues in recent years. In Clinton v. Jones (1997), for example, the Court had to determine whether, and to what extent, a sitting President is immune from private lawsuits seeking damages arising out of unofficial acts that occurred before he took office. Three years later, in Bush v. Gore, the Court played a pivotal — and unprecedented — role in determining the outcome of the 2000 presidential election. The ultimate significance of these decisions, both to the Court and to the country, remains to be seen.