Rutledge was rejected and Washington named Patrick Henry to the Court. Now an old man, Henry declined to serve. Finally, Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut accepted Washington’s offer to become Chief Justice.

The Jay Treaty continued to infuriate Americans who thought it too favorable to Britain. Feeling still ran high in 1796 as the Court reviewed the case of Ware v. Hylton. Many British subjects had claims against Americans from contracts made before the revolution, and treaty provisions required their payment.

In his only argument before the Supreme Court, John Marshall defended a Virginia law abolishing payments to British creditors; he lost. A treaty of the United States must override the law of any state, ruled the Justices. The Nation pledged its word — it must keep faith — a landmark decision that has held for two centuries.

But two raucous choruses were shouting abuse at each other when the Court met at Philadelphia for the last time, in August 1800. The government was moving to a new site by the Potomac, where no one had ever planned a judiciary building. In 1801 Congress loaned the Court a little ground-floor room in the unfinished Capitol; it crowded the Justices for seven years.

Changing capitals was easier than changing the government. With vast excitement, the people were tussling over an issue the Constitution ignored; painfully, nervously, they were working out a two-party system.

Against the Federalists, “the good, the wise, and the rich,” the party of Washington and Adams, stood the admirers of Vice President Thomas Jefferson — “the Man of the People.” Calling themselves Republicans, the Jeffersonians wanted to give the people more of a voice in government; they praised the ideals of the French Revolution, and they had nothing but distrust for Britain.

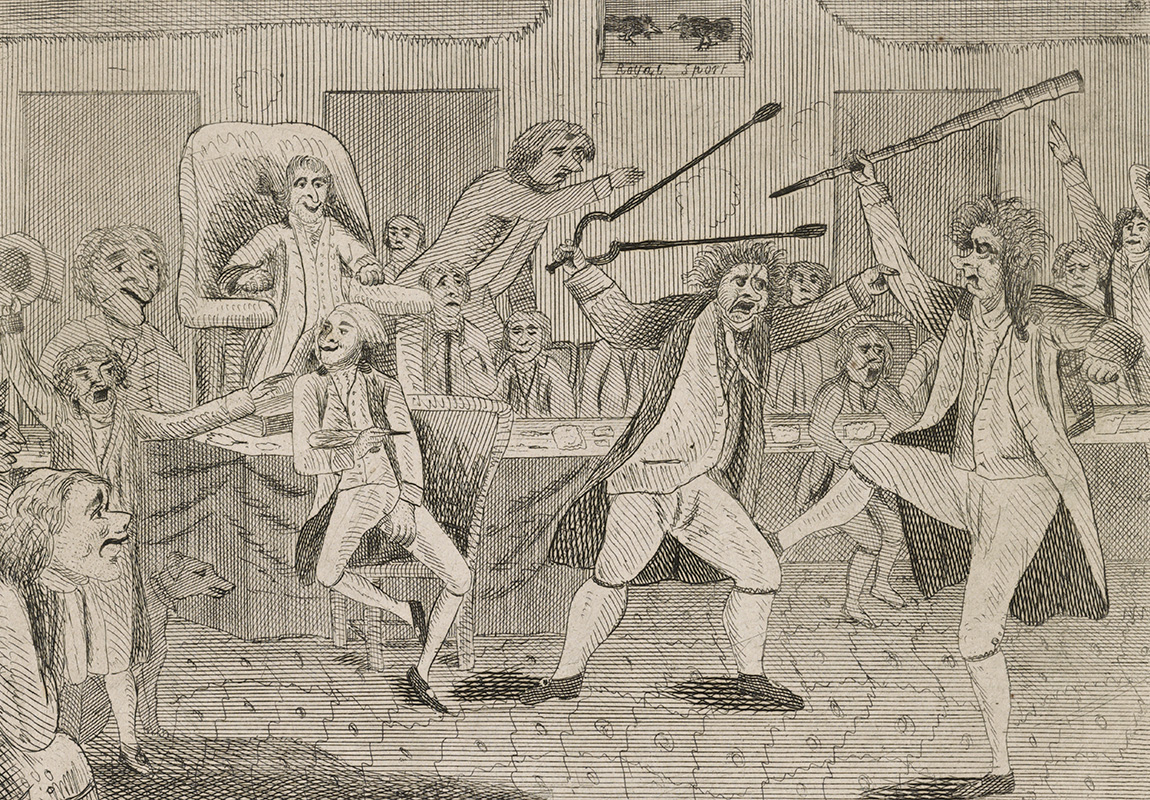

During John Adams’s term as President, the French insulted the administration from abroad and the Republicans criticized it at home. Federalists had run the new government from the first. They feared attacks on themselves as attacks on the new Constitution. Hearing French accents in every critical sentence, they passed the Sedition Act of 1798.

The law endangered anyone who spreads “false, scandalous and malicious” words against the government or its officers, to bring them “into contempt or disrepute.” It would expire with Adams’ term of office on March 3, 1801.

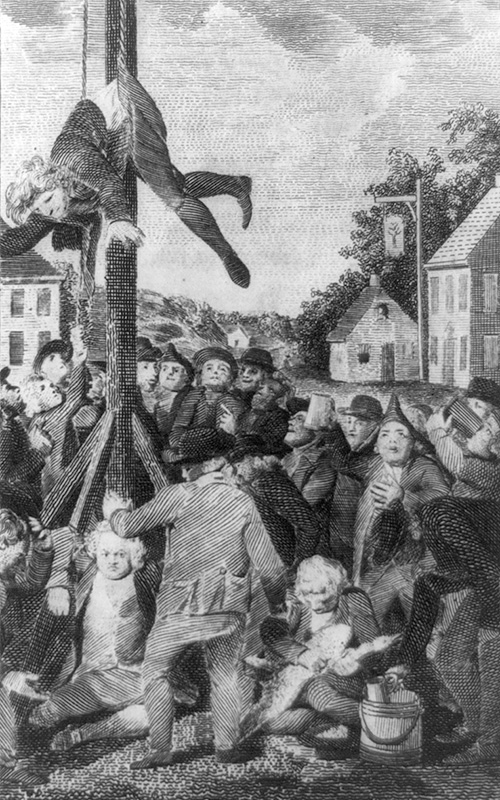

Finding fault with men in office was already an old American custom, writes one historian; “indeed, it had become an essential part of the pursuit of happiness.” Supreme Court Justices presided at trials on circuit and sent Republican journalists to jail for sedition. But the Republicans kept on criticizing, and shouting “Tyranny!” The Federalist answered with furious cries of “Treason!”

In the 1800 elections the “Lock Jaw” Federalists were routed — “Mad Tom” Jefferson would be President, and his followers would control Congress.

Gloomily, the Federalists hoped that judges could save the Constitution from these “radicals.” Chief Justice Ellsworth was ailing; he resigned. Jay refused to serve again. So Adams gave his Secretary of State, John Marshall, to the Supreme Court. He forced a reluctant Senate to confirm the appointment.