“What a potato hole of a place, this!” A western lawyer, seeing the Court’s first-floor room in the Capitol in 1859, had exclaimed. He thought the Justices should be “got up above ground” for some fresh air and daylight. Once they moved to their new courtroom, the old Senate Chamber, in December 1860, they had more space than ever before, with 12 rooms for their officials and records.

Congress added a tenth seat to the more spacious Court in 1863, and Lincoln appointed Stephen J. Field of California. In 1864, to succeed Taney as Chief Justice, he chose Salmon P. Chase of Ohio.

Ambitious and able, Chase had won fame for defending runaway slaves, served one term in the Senate and two as Governor of Ohio when Lincoln named him Secretary of the Treasury in 1861. Inexperienced in finance, Chase grappled with war costs—more than $1,000,000 a day. He planned a radical new tax on income, a new system of national banks. But plans for legal tender notes, the famous “greenbacks,” upset him. War or no war, he thought, the Constitution forbade such paper money.

Lincoln sent Chase a message “not to bother himself about the Constitution . . . I have that sacred instrument here at the White House, and I am guarding it with great care.” Reluctantly, Chase agreed.

Gossip described him addressing a mirror: “President Chase.” His own hopeful publicity described his qualifications for Lincoln’s place in 1864; the people declined his offer, and in June Lincoln accepted his resignation from the Treasury. Then Chase found himself named Chief Justice by the Chief Executive he had tried to supplant.

In the autumn of 1864, Lambdin P. Milligan of Indiana, a civilian, had been tried before a military commission. He was convicted of conspiring to overthrow the government, and sentenced to hang. With Milligan’s petition for a writ of habeas corpus, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Chase considered the problem of military power over civilians.

During “the late wicked Rebellion,” Lincoln had authorized such military tribunals. But, said the Justices, the federal courts in Indiana were always open to try cases like Milligan’s. Therefore, under the Constitution, no military courts could try them; and, however shocking the charges, the defendants kept their rights under law.

At liberty again, Milligan sued the military for false imprisonment, and a jury awarded him damages—five dollars.

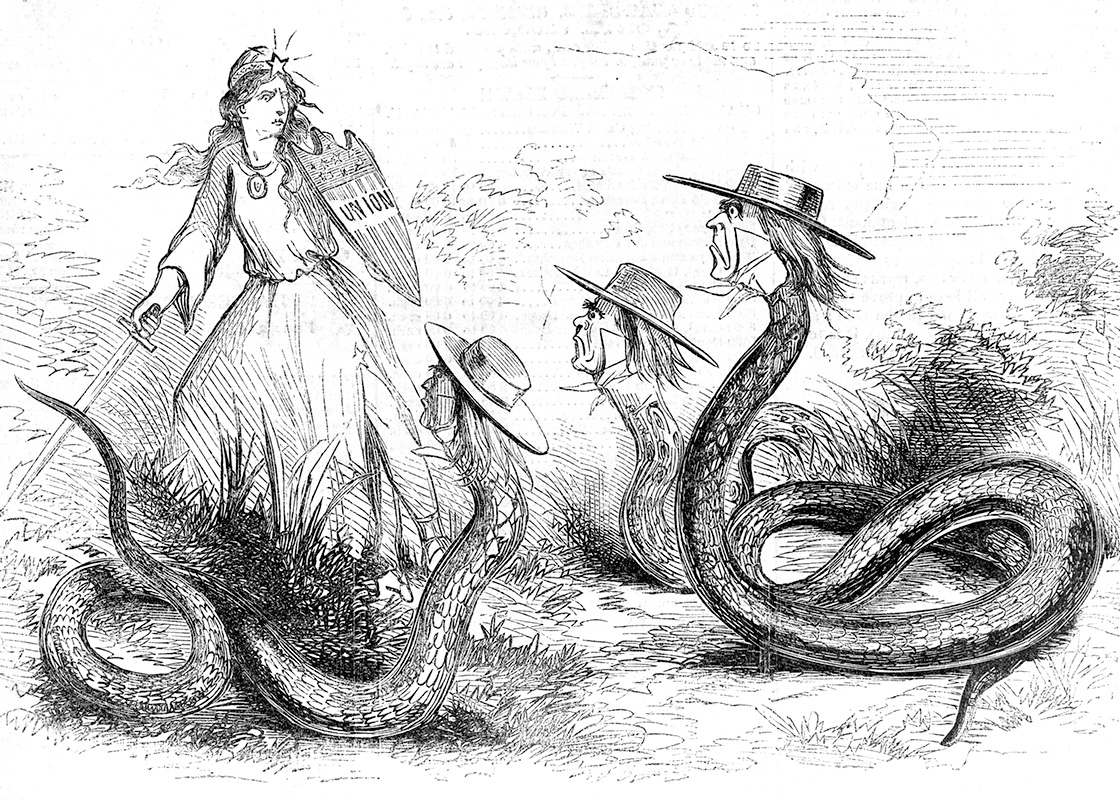

Under Radical Republican leaders, the postwar Congress seemed determined to reconstruct the whole American government. One Representative talked of an amendment to abolish the Supreme Court; another warned President Andrew Johnson “that as Congress shall order he must obey.”

Striking at Johnson, Congress lowered the number of Justices from ten to eight; and to protect the Reconstruction laws, it limited the Court’s jurisdiction on appeals.

It was the Senate, not the Court, that tried the most dangerous cases of those bitter years, the impeachment of the President.

Johnson’s political enemies wanted a quick conviction. The Constitution, however, required the Chief Justice to preside; and Chase insisted on presiding as a judge, while the Senate tried legal issues as a court should. The Radicals had to let him rule on points of law; Chase gave the President’s lawyers a chance to be heard. Johnson escaped conviction by one vote.

Those same bitter years saw amendments altering the Constitution. In 1865 the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery; in 1868 the Fourteenth Amendment defined United States citizenship and defended it against infringements; in 1870 the Fifteenth Amendment barred racial limits on the right to vote.

While the South struggled with carpetbaggers and Ku Klux Klansmen, the rest of the country rushed into the splendors and scandals of the Gilded Age. Wartime greenbacks went cheap and debtors liked them; creditors wanted gold, and Chase and his Associates had to bother themselves about currency and the Constitution.

Hepburn v. Griswold, a private lawsuit, came before them in 1867, challenging the Legal Tender Act of 1862 and the Nation’s money. Justice Wayne had died; when the remaining Judges discussed the case they divided four to four, as sharply as the rest of the country. Chase was one of those who opposed the law. If you had promised in 1861 to pay a debt in gold, he said, you could not force greenbacks on your creditor; Congress could not impair such contracts.

Then Grier, aged and sadly feeble, changed his vote so that Chase spoke for a majority. Somewhat awkwardly, the Chief Justice struck down in 1870 the law he had reluctantly defended at the Treasury.

Dissenting, Justice Miller insisted: Congress had all the powers it needed to fight a war, including power to change the currency.

Although the Court’s decision applied to contracts made before February 25, 1862, it implied that greenbacks might not be valid for later contracts. It called in question more than $350,000,000 in greenbacks. The government fretted. A Boston newspaper protested bitterly against “the country’s being mangled and slaughtered, while the Supreme Court is making experiment upon the laws of currency.”

Grier had resigned; Grant named William Strong and Joseph P. Bradley to the Court. They wanted to hear argument in other legal tender cases; astonished lawyers heard the Justices argue furiously on the bench about reopening the money question. After hearing the new cases in 1871, the two new Justices joined the three dissenters of Hepburn to overrule that decision.

Strong announced that the Legal Tender Act was constitutional; it helped pay for the war, and it saved the Nation. Bradley, concurring, went further: under the monetary power, Congress could provide for paper money even in peacetime emergencies—a view the Court accepted 13 years later.

Angry editors charged that Grant had packed the Court; and even people who liked greenbacks disliked the Court’s reversing itself so thoroughly and so fast.

After the spring term of 1873, Chase died. A Negro guard of honor brought his casket to the Supreme Court Chamber for a state funeral. As it rested on Lincoln’s catafalque, a moment of Presidential honor came to the Chief Justice at last.