The re-argument of school segregation proceeded on schedule in December with 51 amicus curiae, “friend of the court,” briefs—a record number up to that time.

On May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren read the momentous opinion for a unanimous Court: “. . . in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.” The Court ruled that segregation in public schools deprives children of “the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.”

The May 1954 rulings affected 21 states and the District of Columbia. But the Justices did not order specific changes at once. They gave all the states affected a chance to be heard in yet another argument, this one on appropriate remedies.

Some states filed briefs. Oklahoma explained that it would have to rewrite its tax laws; North Carolina and Florida included long reports on public opinion.

On May 31, 1955, Chief Justice Warren again spoke for a unanimous Court. The cases would go back to the lower courts; these would review the work of local officials facing the problem of unprecedented change. Desegregation would now proceed “with all deliberate speed.”

“Jurors—plain people—have manfully stood up in the defense of liberty” on many occasions, wrote Justice Hugo Black in 1955. To deprive 3,000,000 persons of the safeguards in trial by jury went beyond the power of Congress, he declared; a law to do so was unconstitutional, and Miss Audrey M. Toth had won against Donald A. Quarles, Secretary of the Air Force.

Honorably discharged from military service in December 1952, her brother Robert came home to Pittsburgh and got a job in a steel plant. Air Force police arrested him at work in May 1953, and flew him to Korea for court-martial on charges of murdering a Korean the previous September.

At Miss Toth’s petition, a district court issued a writ of habeas corpus, and the Air Force brought back its prisoner. A court of appeals ruled against him, and then the Supreme Court took the case.

Like Toth, any veteran might be hustled off for court-martial “for any alleged offense” in service, Black warned—if the Court found power for Congress to say so. The Court did not. To provide for justice in such cases, said Black, Congress could give jurisdiction to civilian courts by law.

At an Air Force base in Oxfordshire, England, a sergeant’s wife was saying she had killed her husband the night before.

Delusions, thought the Air Force psychiatrist; he knew how she had grown up wretched in a poor and broken home, how her husband squandered money and drank. But he sent men to investigate; they found her husband’s body.

Under psychiatric and prenatal care, she waited in a hospital until a court-martial convicted her of premeditated murder and sentenced her to life at hard labor. Flown back to America in 1953, she bore her third child in a federal prison for women.

The Court of Military Appeals ordered a new trial; in 1955 doctors found her sane; then the Supreme Court agreed to hear argument that the Uniform Code of Military Justice denied her constitutional rights to a jury trial under the Sixth Amendment. With her case they took another that raised the same legal issues.

Working under pressure as the term was closing, the Court reached these cases and announced the validity of military trials for civilian dependents abroad. Justices Warren, Black, and Douglas noted dissent; Justice Frankfurter, a “reservation” of opinion.

Then, as it rarely does, the Court granted a petition for rehearing; in 1957 six Justices agreed to reverse the decisions. Congress could not deprive civilians of the safeguards in the Bill of Rights, Justice Black insisted. Under the new ruling, courts-martial may not try mothers, wives, or children of servicemen for crimes carrying a death penalty.

Extending this rule in a series of cases, the Court stopped court-martial trial of dependents for lesser crimes, and of civilian employees abroad for all crimes.

For himself and a codefendant, a man named Griffin wrote a petition: because of their “poverty,” they could not pay for a transcript of their trial for armed robbery and without this record they could not appeal in Illinois courts. Griffin thought the Fourteenth Amendment forbade justice “only for ‘Rich.’” So did the Justices, in 1956. They ordered Illinois to give Griffin a free transcript; they gave “equal protection of the laws” a new value. If a man with money can buy a hearing because his state offers a right of appeal, that state must help a man without money.

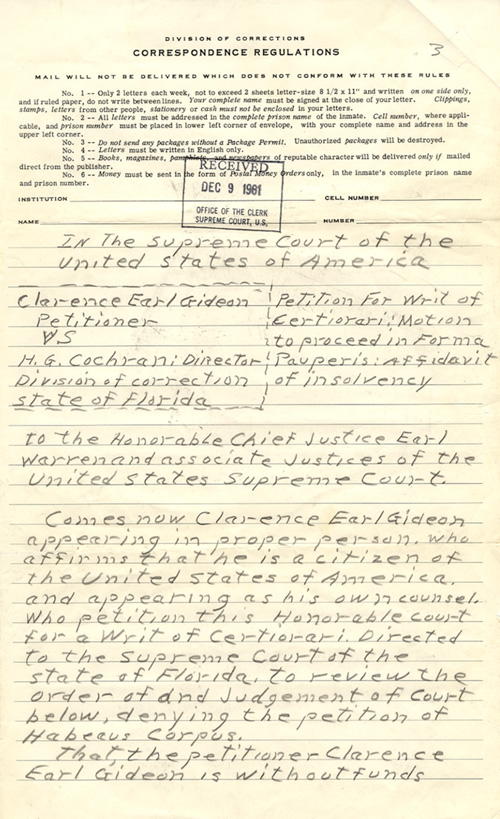

Accused of breaking into a poolroom in Panama City, Florida, in 1961, Clarence Earl Gideon tried to get a court-appointed lawyer, and failed. He tried to defend himself, and failed. He tried to persuade the Supreme Court to review his case, and succeeded. The Court appointed Abe Fortas of Washington to argue Gideon’s claim that without a lawyer no man gets the fair trial the Constitution demands.

Before the Justices, Fortas stressed the confusion any layman would feel when Florida said: “Apply the doctrine of Mapp v. Ohio. Construe this statute of the State of Florida. Cross-examine witnesses. Call our own witnesses. Argue to the jury.”

Florida’s attorney argued that the issue should be left to the states. But all nine Justices agreed that no man should have to defend himself against a felony charge, trying to apply precedents he never heard of and construe laws he never read. If a defendant has no money for a lawyer, the state court must appoint one for him. On retrial, a Florida jury acquitted Gideon.

As Justice Potter Stewart had pointed out, Florida wouldn’t have let Gideon represent anyone else as an advocate in its courts. But as lawyers and newspapers said, in the Supreme Court Gideon could stand for anyone who happened to be poor.

Dollree Mapp may stand for anyone who thinks a government should obey its own laws.

To protect the people’s right to security, the Fourth Amendment requires federal officers to have specific and detailed warrants for searches and arrests. The states have had similar requirements.

But for many years officers disregarded this. If they broke into a home and seized property contrary to law, prosecutors could use it as evidence in court to convict its owner—government could, and did, break the law to its own advantage.

In 1914, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Edward D. White had announced that if federal officers seize things illegally, federal judges must not admit such things in evidence in their courtrooms. But that decision did not bind state courts. Until 1961 the Court left states free to admit such evidence if they chose.

When police arrived at Mrs. Mapp’s home in Cleveland, Ohio, on May 23, 1957, she refused to admit them unless they had a warrant. Three hours later they forced a door, handcuffed Mrs. Mapp for being “belligerent,” and searched the house thoroughly, hunting for a person “wanted for questioning” and for evidence of gambling. Finding books they thought obscene, they arrested her for having these.

On trial, Mrs. Mapp offered evidence that a boarder had left the books, some clothes, and no forwarding address. The police did not prove they had ever had any warrant. But Mrs. Mapp got a prison sentence. Ohio’s highest court upheld it.

Reviewing Mapp v. Ohio, the Supreme Court decided in 1961 to bar the doors of every courtroom—state as well as federal—”to evidence secured by official lawlessness.” The Fourth Amendment sets standards for search and seizure, said its opinion, and the Fourteenth requires judges to uphold them in every state of the Union. In closing the courtroom doors, the Justices guarded the doors of every home.

Taxation without representation is tyranny, American colonists were saying angrily in the 1760’s. In the 1960s, voters in American cities were saying the same thing.

City voters sent some lawmakers to Congress and the state legislatures, of course; but in many states rural voters—a minority of the population—sent more. People had been moving from farms to cities, but electoral districts had not changed.

In 1950, one Vermont representative spoke for 49 people, another for 33,155. In Connecticut, a mere nine and one-half of the people could elect a majority of the state’s representatives. By 1955, the Colorado legislature was giving Denver $2.3 million a year in school aid for 90,000 children; it was giving a semirural county $2.4 million for 18,000 pupils.

Although the Supreme Court had decided cases on voting frauds and discrimination in state primary elections, it had dismissed a case on Congressional apportionment in 1946. “Courts ought not to enter this political thicket,” Justice Felix Frankfurter had warned; federal judges had obeyed.

Nevertheless, Charles W. Baker of Memphis, Tennessee, and nine other qualified voters filed a suit against Joe C. Carr, Secretary of State, and other officials. They asked a federal court to order changes in the state’s election procedure. The Tennessee constitution said electoral districts should be changed every ten years, but the General Assembly had not passed a reapportionment law since 1901.

When the lower court dismissed Baker v. Carr, the Supreme Court accepted it. The Justices studied briefs with maps of voting districts, and a special brief for the United States; they heard argument twice. Then, setting precedents aside, the Court decided that minority rule in state legislatures is a matter for judges to review.

Justice William Brennan spoke for the majority. If a state lets one person’s vote count for more than another’s because they lie in different districts, that state denies its citizens equal protection of the laws. Citizens wronged by “debasement of their votes” may go to court for help.

The Warren Court formal photograph taken in 1962. Front row: (left to right) Associate Justices Tom C. Clark, Hugo L. Black, Chief Justice Earl Warren, Associate Justices William O. Douglas, and John Marshall Harlan. Back Row: (left to right) Associate Justices Byron F. White, William J. Brennan, Potter Stewart, Arthur J. Goldberg.

In 1967, history was made when Thurgood Marshall became the first African American appointed to the Supreme Court. This photograph was taken while the Court was waiting to take the formal photograph. Front row: (left to right) Associate Justices John Marshall Harlan, Hugo L. Black, Chief Justice Earl Warren, Associate Justices William O. Douglas, William J. Brennan, Jr. Back row (left to right) Associate Justices Abe Fortas, Potter Stewart, Byron R. White, and Thurgood Marshall.

In March 1962, the Supreme Court sent Baker’s case back to the district judges for them to decide. By November, voters in 30 of the 50 states were suing in state as well as federal courts for new voting districts.

A case from Georgia brought the issue of Congressional apportionment before the Supreme Court again; it ruled in 1964 that Congressional districts should be equal in population.

Alabama appealed to the Supreme Court when district court judges rejected three reapportionment plans for the state. Sustaining the lower court, the Justices listed new rules for a state legislature. Both houses must be based on population, they said; and if districts differ in population, the Court would not find the differences valid for geographic, historic, or economic reasons alone.

“Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our Country.”

As supervisors of the state’s public education under New York law, the Board of Regents wrote this classroom prayer in 1951. Formal religion has no place in public schools, they said, but “teaching our children, as set forth in the Declaration of Independence, that Almighty God is their Creator” would give the “best security” in dangerous days. They recommended their prayer to local school boards; some accepted it, including the board in New Hyde Park, which voted in 1958 for the prayer to open each school day.

Some parents objected; they feared that if government may regulate or require any religious practice in a public school it gains power over matters that should be free. Steven I. Engel and four other parents asked a New York court to order the prayer discontinued.

William J. Vitale, Jr., and other board members replied that prayer gave moral training for good citizenship. On request, they said, any child would be excused from praying.

By adopting the Regents’ prayer, schools did not prefer or teach religion, the courts in New York held; but schools must not compel any child to pray. In 1961 the Supreme Court accepted Engle v. Vitale for review.

Justice Hugo L. Black gave the Supreme Court’s opinion in June 1962: A “solemn avowal of divine faith,” the Regents’ prayer was indeed religious—and unconstitutional, because the authors of the Constitution thought religion “too personal, too sacred, too holy,” for any civil magistrate to sanction. No government should compose official prayers for Americans to recite.

When lawyers for two other school boards appeared before the Court in 1963, they praised the ruling in Engel v. Vitale but insisted that it did not apply to their cases. In their schools official prayers had no place, although pupils read the Holy Bible and recited the Lord’s Prayer every day unless parents wanted them excused.

Professed atheists, Mrs. Madalyn E. Murray of Baltimore and her son William challenged the school exercises for favoring belief over nonbelief. Mr. and Mrs. Edward L. Schempp of Abington, Pennsylvania, wanted to teach their children Unitarian beliefs without “contradictory” practices at school. As taxpayers and parents of students, they had standing to sue.

Reviewing these two cases, the Supreme Court declared again that no state may prescribe religious ceremonies in its schools, that the Constitution stands between the government and the altar.

In 1969, Chief Justice Earl Warren stepped down after presiding over the Court for 16 years, a period marked by controversial decisions and impassioned public debate. There were heated conflicts over desegregation remedies formulated under the decision in Brown v. Board of Education; over what was called a revolution in the rights of criminals; and over issues of religious freedom, guaranteed in the first 16 words of the Bill of Rights.