At the end of the October Term 1936, the Justices dispersed as usual in June. They needed a break. The Court was under attack by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Court-packing bill, which threatened to add a new Justice for each one over the age of seventy who refused to retire, under the trumped-up premise that the “Nine Old Men” (average age: seventy) were unable to keep up with their workload. Roosevelt had been frustrated by the Court’s striking down legislation designed to alleviate the country’s economic tailspin. Yet, by the time he announced the plan in February, a Court majority had finally begun upholding a few of his New Deal initiatives — thanks mainly to a fifth vote provided by Owen J. Roberts. After hammering out remarkable opinions all spring, where did the Justices go to recharge and escape the Washington heat?

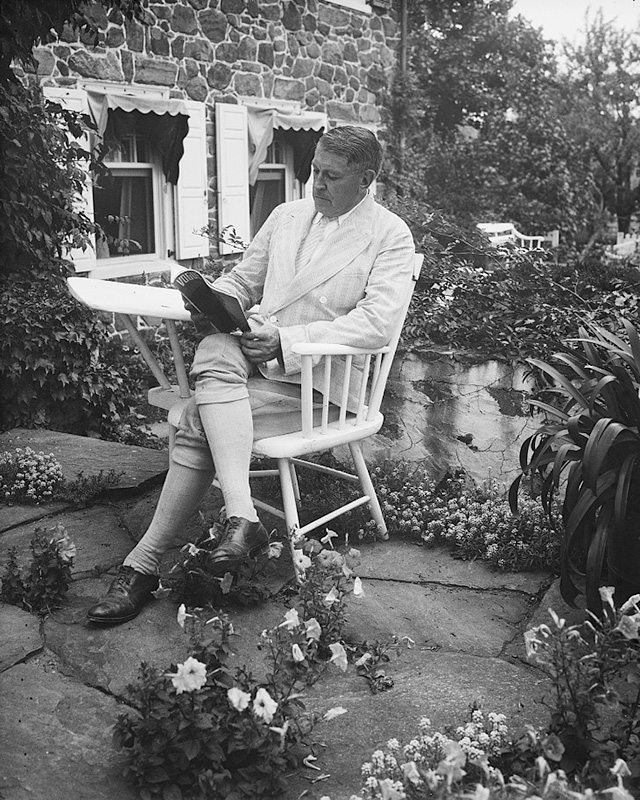

Agricultural pursuits attracted several Justices. In particular, swing voter Justice Roberts returned to being a gentleman farmer in the summer. He kept a prize herd of dairy cows at his sprawling homestead in Chester County, Pennsylvania, near Valley Forge. Justice Willis Van Devanter, whose surprise announcement that he would retire at the end of the 1936 Term deflated the conservative bloc, of which he had been the intellectual leader, retreated to his 700-acre farm near Ellicott City, Maryland. There he grew corn, oats, and wheat, and raised livestock, including thoroughbred Hampshire hogs. Having grown up on a Minnesota dairy farm, Justice Pierce Butler also loved rural life. He spent his weekends at a Blue Ridge mountain community on the Maryland-Pennsylvania border, where he tended his livestock and worked on his golf game during the summer.

Two Justices ventured abroad. George Sutherland, born in Buckinghamshire, England, returned to visit his birthplace and then drove with his wife through England and Scotland before heading over to the Continent. They enjoyed taking long walks in the hills. James C. McReynolds, a bachelor, returned first to his hometown of Elkton, Kentucky, to visit relatives. Then he took a steamship to Europe in the company of friends with whom he travelled abroad each summer.

Two others had summer homes on Cape Cod. Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, having adeptly maneuvered during the Court-packing crisis, motored with his wife to their ocean-front home in Osterville. Louis D. Brandeis spent the entire summer at his modest grey-shingle house in Chatham, where he and his wife enjoyed canoeing, tennis, and being with their children and grandchildren.

Justice Harlan Fiske Stone and his wife made a quick trip to Mexico before settling in their cottage on Isle au Haut, a remote island in Penobscot Bay, Maine, accessible only by ferry. Stone liked to row his dory along the cragged coastline and eat lobster.

As usual, Benjamin Cardozo returned to his home in Rye, New York, where he enjoyed the company of friends. A bachelor, Cardozo particularly relished summer, finding life on the Court lonely and difficult.

The Court-packing bill fizzled out in July. The Justices were relieved that the bill’s threat no longer loomed when they returned to start the new Term in October. They also found they had a new bench-mate filling Van Devanter’s seat, an Alabama senator who had fully supported the president’s agenda. As a Justice, Hugo L. Black would help cement what came to be called the Constitutional Revolution of 1937-38. But the long summer recess had allowed both for political events to play out and for the Justices to feel refreshed before tackling more New Deal cases. Brandeis phrased it best when he touted the necessity of vacation: “I can do 12 months’ worth of work in 11, but not in 12.”

Front row: Justices Brandeis and Van Devanter, Chief Justice Hughes, and Justices McReynolds and Sutherland. Back row: Justices Roberts, Butler, Stone, and Cardozo.

This essay was originally published by Scotusblog in 2011