Under new Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, the Supreme Court again reviewed a conviction. In this case, a jury had found Hans Max Haupt, a naturalized citizen, guilty of treason. Haupt’s son, Herbert, one of eight originally convicted saboteurs, had already been executed. Witnesses swore that Hans Haupt had sheltered his son for six days in his Chicago apartment; he had helped him buy a car; he had helped him try to get back a job at a plant making lenses for the secret Norden bombsight. All these actions were harmless, even if proved, Haupt’s lawyers argued.

Again Justice Robert H. Jackson wrote the majority opinion. The trial judge had properly instructed the jury, he said, to decide if Hans Haupt meant only to help his son or if he meant to help Germany against the United States. The jury had found him a traitor, and in law they had sufficient evidence.

Meanwhile, in another long series of decisions, the Court was defining the constitutional rules for fair criminal trials in state courts.

Held for days against Indiana law, questioned for hours by relays of policemen, a man named Watts finally said something that convicted him of murder; in 1949 the Court ruled that such coercion also denies due process—if a man’s own words may cost his life he must speak at his own choice.

As the United States entered the second half of the twentieth century, forces were gathering which would lead in a few short years to a historic reversal. Since 1896 the “separate but equal” doctrine upheld by the Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson had been the law of the land; under it many states and the District of Columbia had operated racially segregated school systems.

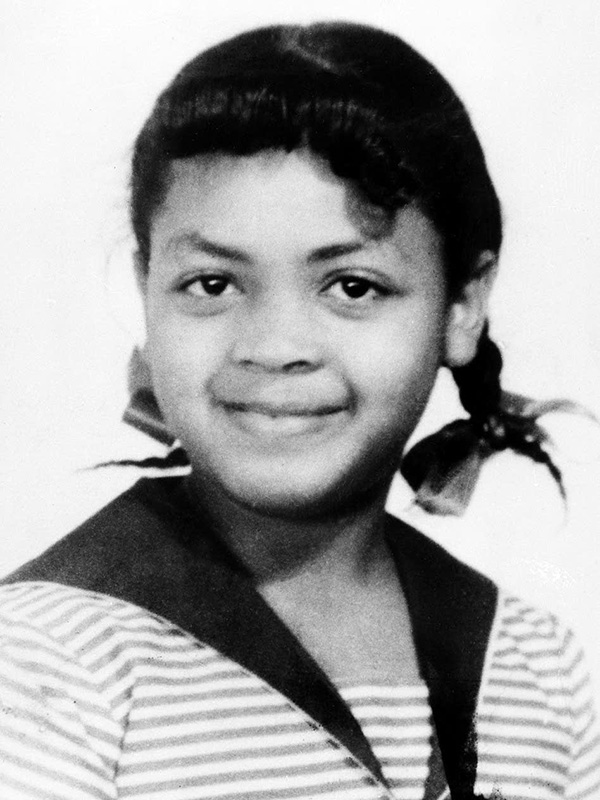

The beginnings of change were deceptively modest. In 1951 Oliver Brown of Topeka, Kansas, sued the city school board in behalf of his eight-year-old daughter Linda Carol. She had to cross railroad yards to catch the bus for a black school 21 blocks away; her father wanted her in the white school only five blocks from home.

Three federal judges heard testimony on teachers, courses of study, buildings; they heard lawyers for Brown and 12 other black parents argue that the Kansas law permitting segregation violated the Fourteenth Amendment. Finding the schools substantially equal, the judges ruled against Brown; they said that Plessy controlled the case.

Ten-year-old Harry Briggs, Jr., and 66 other black children had filed a similar suit, through their parents, against school authorities in Clarendon County, South Carolina. The County was spending $395,000 for 2,375 white pupils, $282,000 for 6,531 black pupils. All the white students had desks; two black schools had no desks at all.

The federal court that heard the Briggs case ordered Clarendon County to “equalize” its schools as soon as possible; but, relying on Plessy, it refused to order black pupils admitted to white schools, or to rule South Carolina’s segregation law invalid.

The Supreme Court heard argument in December 1952, on the Brown and the Briggs cases, combining them with an almost identical case from Prince Edward County, Virginia, and one from Delaware.

Delaware’s court of equity had found separate black schools inferior and ordered black children transferred to white schools at once; its highest court had sustained the order, and school officials had sought review in the Supreme Court.

Briefs for all the black litigants included data from psychologists and social scientists. Since Louis D. Brandeis filed his famous brief for Oregon in 1908, lawyers had offered “non-legal” facts to defend a challenged law; now they offered such material to attack state laws. Records from the lower courts printed the testimony of expert witnesses explaining why they thought legal segregation harmed black children.

In June 1953, the Court ordered a reargument. Then, on September 8, Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, aged 63, died unexpectedly of a heart attack. President Eisenhower moved promptly to appoint his successor, Earl Warren, the popular Governor of California.