Congress had passed the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938. It banned child labor, regulated hours, and set minimum wages—25 cents an hour—in interstate commerce. United States v. Darby Lumber Co. brought the law before the Court under Chief Justice Harlan F. Stone in 1941.

If the Justices followed the child-labor decisions of 1918 and 1922, they would veto the law; but all nine called it valid.

West Virginia law required all schools to teach “Americanism,” and in 1942 the State Board of Education ordered all teachers and pupils to salute the flag. A child who refused might be punished as a “delinquent,” his parents might be fined or jailed.

Walter Barnette and other Jehovah’s Witnesses with school-age children sued for a federal injunction against these penalties; in 1943 the Supreme Court heard the case argued.

On Flag Day, June 14, the Court flatly overruled and repudiated the earlier Gobitis decision. For the majority, Justice Robert H. Jackson rejected the idea that a child’s forced salute would foster national unity. He signaled out as a “fixed star in our constitutional constellation” this fact—”no official, high or petty,” can prescribe orthodoxy in politics, nationalism, or religion, for any citizen.

Justice Felix Frankfurter still upheld the state’s action against his own “purely personal” view, saying: “One who belongs to the most vilified and persecuted minority in history is not likely to be insensible to the freedoms guaranteed by our Constitution.”

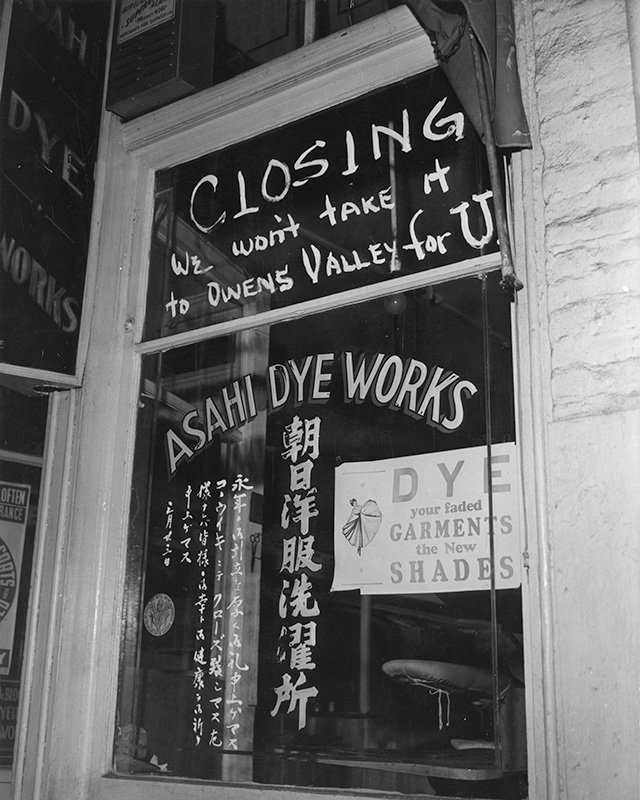

“In this solemn hour we pledge our fullest cooperation to you, Mr. President, and to our country,” said a telegram to President Roosevelt, December 7, 1941, from the Japanese American Citizens League, at news of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

By the spring of 1942 such citizens were a vilified minority in their own country. In February, the President signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the War Department to remove “any and all persons” from military areas it might name; Congress approved in a law passed March 21. The Western Defense Command ordered everyone of Japanese ancestry to stay indoors from 8:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m. In May, the Army ordered such persons to report for evacuation to “relocation centers”—detention camps.

Gordon K. Hirabayashi, a senior at the University of Washington, thought it was his duty as a citizen to disobey both these orders, to defend his constitutional rights. Convicted and sentenced to three months in prison, he applied to the Supreme Court.

Chief Justice Stone spoke for all nine in June 1943: the curfew was within the war power of the President and Congress. Concurring, Justice William O. Douglas wrote that the Court did not consider the wisdom of the order; Justice Frank Murphy insisted that the government could take such measures only in “great emergency.”

In Korematsu v. United States, argued in October and decided on December 18, 1944, the Court upheld an Army order banishing civilians of Japanese ancestry from the west coast—adults, foster children in white homes, citizens “with as little as one-sixteenth Japanese blood.” Justice Hugo L. Black wrote the majority opinion, mentioning Toyosaburo Korematsu’s unquestioned loyalty. Orders affecting one racial group are “immediately suspect,” said Black, but the Court would accept the order “as of the time it was made,” under the war power.

Three Justices dissented, calling the order “a clear violation of Constitutional rights,” “utterly revolting among a free people.”

That same day, the Court unanimously ordered the Central Utah Relocation Center to release Miss Mitsuye Endo. The War Relocation Authority had conceded she was a loyal, law-abiding citizen, but it had not allowed her to leave the center freely.

Justice Douglas’s opinion warned that power to defend the community is not power to detain trustworthy citizens. Federal courts may issue writs of habeas corpus in such cases, he said. “Loyalty is a matter of the heart and mind,” added Douglas, “Not of race, creed, or color.”

As defense council for Richard Quirin and seven other prisoners, Col. Kenneth C. Royall and Col. Cassius M. Dowell decided that to obey one order of their commander-in-Chief they had to defy another. Their clients, all German-born, had lived in America but returned before Pearl Harbor to study sabotage techniques at a school near Berlin.

Five nights later, Herbert Haupt, Werner Thiel, Edward Kerling, and Hermann Neubauer landed safely at Ponte Vedra Beach, Florida, from another U-boat. None of the saboteurs was successful. On June 27, the FBI announced the arrest of all eight.

President Roosevelt appointed a military commission to try them as spies under the Articles of War; and Colonels Royall and Dowell to defend them. He issued a proclamation closing all civilian courts to such enemies, but the defense decided, in duty to their clients, to disobey this. Challenging the commission’s legal authority, they sought writs of habeas corpus from the Court.

After two days of hearing and questioning lawyers for both sides, the Court said that Congress, in the Articles of War, had provided for commissions to try such cases; that the President had lawfully appointed one; that the writs would not issue.

But in finding for the President, the Supreme Court set another precedent—a proclamation from the White House could not close the doors of the Court. An executive order would not annul its power to review government actions under law.

The President announced on August 8 that all the saboteurs had been convicted, six executed. Two who had cooperated with the FBI went to prison at hard labor.

Bridges and aluminum plants survived the saboteurs’ visit unharmed; a friend and a father did not. From Werner Thiel’s days in New York before his arrest, when he was watched by the FBI, came Cramer v. United States. For the first time the Supreme Court reviewed a conviction for treason; a five-to-four vote decided that the conviction could not stand.

Justice Robert H. Jackson, for the majority, explained why. The Constitution outlines the law of a most intricate crime in two sentences “packed with controversy and difficulty,” he said. Treason against the United States lies “only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.” Unless a person confesses “in open Court” or two witnesses testify “to the same overt Act” of treason, he cannot be found guilty.

The jury that convicted Anthony Cramer, a naturalized citizen, heard how he met two of the saboteurs, Thiel and Keating, “enemies of the United States,” at an inn and a cafeteria. Two witnesses swore that they drank and talked “long and earnestly.” But no one proved what they said.

The jury had no evidence that Cramer gave the enemies shelter or advice “or even paid for their drinks.” Before the war, Thiel and Cramer had shared “a small and luckless delicatessen enterprise.” If they met in public “to tipple and trifle” this did not prove Cramer’s treason in law.

Acts innocent by nature may serve a treasonous plan, Justice William O. Douglas had insisted for the four dissenters, one of whom was Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone.

Stone served the Court as Chief Justice until April 22, 1946. President Harry S. Truman nominated Fred M. Vinson as his replacement.