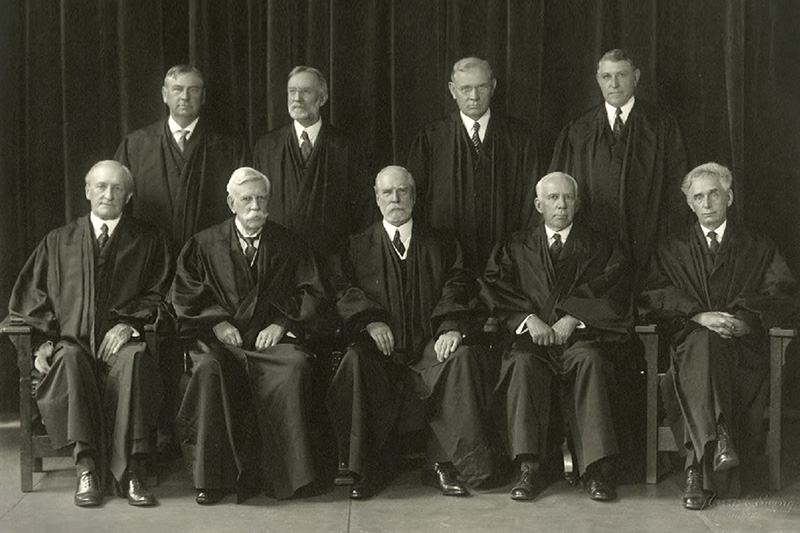

Nicknamed the “roving Justices,” new Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts sometimes joined the “four horsemen”–Justices George Sutherland, Pierce Butler, James C. McReynolds, and Willis Van Devanter–sometimes joined three Judges more willing to accept laws however meddlesome. These three were Louis D. Brandeis, Harlan Fiske Stone, and Oliver Wendell Holmes until he retired in 1932. Benjamin N. Cardozo succeeded him, and often voted with Brandeis and Stone.

In 1925, while the Court was deciding the Benjamin Gitlow case, Minnesota legislators were passing a new statute. It provided that a court order could silence, as “public nuisances,” periodicals that published “malicious, scandalous, and defamatory” material.

“Unfortunately we are both former editors of a local scandal sheet, a distinction we regret,” conceded J. M. Near and his partner in the first issue of the Saturday Press, but they promised to fight crime in Minneapolis. They called the police chief a “cuddler of criminals” who protected “rat gamblers.” They abused the county attorney, who sued Near; the state’s highest court ordered the paper suppressed.

Citing the Schenck and Gitlow decisions, Near’s lawyer appealed to the Supreme Court, which struck down the state law in 1931.

For four dissenters, Pierce Butler quoted with evident distaste Near’s outbursts at “snake-faced” Jewish gangsters; peace and order need legal protection from such publishers, Butler insisted.

For the majority, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes analyzed this “unusual, if not unique” law. If anyone published something “scandalous” a Minnesota court might close his paper permanently for damaging public morals. But charges of corruption in office always make public scandals, Hughes pointed out. Anyone defamed in print may sue for libel, he added emphatically.

However disgusting Near’s words, said Hughes, the words of the Constitution controlled the decision, and they demand a free press without censorship. Criticism may offend public officials, it may even remove them from office; but trashy or trenchant, the press may not be suppressed by law.

How citizens use liberty has confronted the Justices again and again, in cases of violence as well as scandal.

Alabama militia had machine guns on the courthouse roof, said newspaper reports from Scottsboro; mobs had a band playing “There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight”; and amid the clamor, nine black youths waited behind bars for trial on charges of raping two white women.

Victoria Price and Ruby Bates, two white mill workers, were riding a slow freight from Chattanooga on their way home to Huntsville on March 25, 1931. Across the Alabama line, white and black hoboes on board got into a fight; some jumped and some were thrown from the train. Alerted by telephone, a sheriff’s posse stopped the train, arrested the nine Negroes still on it, and took them to jail in the Jackson County seat, Scottsboro. Then Victoria Price claimed they had raped her and Ruby Bates.

Doctors found no proof of this story, but a frenzied crowd gathered swiftly. Ten thousand people, many armed, were there a week later when the nine went on trial.

Because state law provided a death penalty, it required the court to appoint one or two defense lawyers. At the arraignment, the judge told all seven members of the county bar to serve. Six made excuses.

In three trials, completed in three days, jurors found eight defendants guilty; they could not agree on Roy Wright, one of the youngest. The eight were sentenced to death.

Of these nine, the oldest might have reached 21; one was crippled, one nearly blind; each signed his name by “X”—”his mark.” All swore they were innocent.

On appeal, Alabama’s highest court ordered a new hearing for one of the nine, Eugene Williams; but it upheld the other proceedings.

When a petition in the name of Ozie Powell reached the Supreme Court, seven Justices agreed that no lawyer had helped the defendants at the trials. Justice George Sutherland wrote the Court’s opinion. Facing a possible death sentence, unable to hire a lawyer, too young or ignorant or dull to defend himself—such a defendant has a constitutional right to counsel, and his counsel must fight for him, Sutherland said.

Sent back for retrial, the cases went on. Norris v. Alabama reached the Supreme Court in 1935; Chief Justice Hughes ruled that because qualified Negroes did not serve on jury duty in those counties, the trials had been unconstitutional.

“We still have the right to secede!” retorted one southern official. Again the prisoners stood trial. Alabama dropped rape charges against some; others were conflicted but later paroled; one escaped.

The Supreme Court’s rulings stood—if a defendant lacks a lawyer and a fairly chosen jury, the Constitution can help him.

And the Constitution forbids any state’s prosecuting attorneys to use evidence they know is false; the Court announced this in 1935, when Tom Mooney had spent nearly 20 years behind the bars of a California prison.

To rally support for a stronger Army and Navy, San Franciscans had organized a huge parade for “Preparedness Day,” July 22, 1916. As the marchers set out, a bomb exploded: 10 victims died, 40 were injured. Mooney, known as a friend of anarchists and a labor radical, was convicted of first-degree murder; soon it appeared that the chief witness against him had lied under oath. President Wilson persuaded the Governor of California to commute the death sentence to life imprisonment. For years labor called Mooney a martyr to injustice.

Finally Mooney’s lawyers applied to the Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus, and won a new ruling—if a state uses perjured witnesses, knowing that they lie, it violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of due process of law; it must provide ways to set aside such tainted convictions. The case went back to the state. In 1939 Governor Culbert Olson granted Mooney a pardon; free, he was almost forgotten.

When the stock market collapsed in 1929 and the American economy headed toward ruin, President Hoover had called for emergency measures. The states tried to cope with the general disaster. Before long, cases on their new laws began to reach the Supreme Court. Franklin D. Roosevelt won the 1932 Presidential election, and by June 1933, Congress had passed 15 major laws for national remedies.

Almost 20,000,000 people depended on federal relief by 1934, when the Supreme Court decided the case of Leo Nebbia. New York’s milk-control board had fixed the lawful price of milk at nine cents a quart; the state had convicted Nebbia, a Rochester grocer, of selling two quarts and a five-cent loaf of bread for only 18 cents. Nebbia had appealed. Justice Owen Roberts wrote the majority opinion, upholding the New York law; he went beyond the 1887 decision in the Granger cases to declare that a state may regulate any business whatever, when the public good requires it. The “four horsemen” dissented; but Roosevelt’s New Dealers began to hope their economic program might win the Supreme Court’s approval after all.

They were wrong. Considering a New Deal law for the first time, in January 1935, the Court held that one part of the National Industrial Recovery Act gave the President too much lawmaking power.

The Court did sustain the policy of reducing the dollar’s value in gold. But a five-to-four decision in May made a railroad pension law unconstitutional. Then all nine Justices vetoed a law to relieve farm debtors, and killed the National Recovery Administration; FDR denounced their “horse-and-buggy” definition of interstate commerce.

While the Court moved into its splendid new building, criticism of its decisions grew sharper and angrier. The whole federal judiciary came under attack as district courts issued—over a two-year period—some 1,600 injunctions to keep Acts of Congress from being enforced. But the Court seemed to ignore the clamor.

Farming lay outside Congressional power, said six Justices in 1936; they called the Agricultural Adjustment Act invalid for dealing with state problems. Brandeis and Cardozo joined Stone in a scathing dissent: “Courts are not the only agency . . . That must be assumed to have capacity to govern.” But two decisions that followed denied power to both the federal and the state governments.

In a law to strengthen the chaotic soft-coal industry and help the almost starving miners, Congress had dealt with prices in one section, with working conditions and wages in another. If the courts held one section invalid, the other might survive. When a test case came up, seven coal-mining states urged the Court to uphold the Act, but five Justices called the whole law unconstitutional for trying to cure “local evils”—state problems.

Then they threw out a New York law that set minimum wages for women and children; they said states could not regulate matters of individual liberty.

By forbidding Congress and the states to act, Justice Harlan F. Stone confided bitterly to his sister, the Court had apparently “tied Uncle Sam up in a hard knot.”

Tortured and whipped by deputy sheriffs, three men confessed to murder; in 1936 the Supreme Court found that their state, Mississippi, had denied them due process of law.

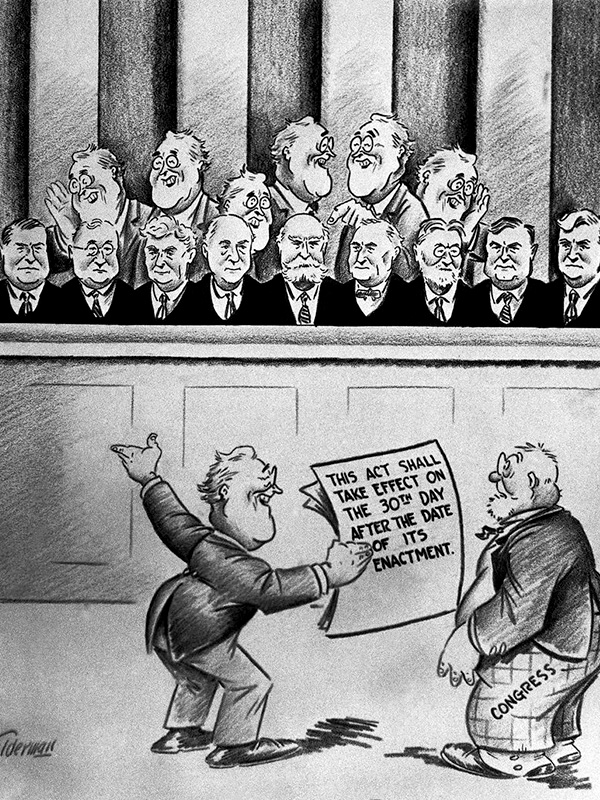

That November Roosevelt won re-election by a margin of ten million votes; Democrats won more than three-fourths of the seats in Congress. The people had spoken. Yet the laws their representatives passed might stand or fall by five or six votes in the Supreme Court. Roosevelt, aware that Congress had changed the number of Justices six times since 1789, sent a plan for court reform to the Senate on February 5, 1937.

Emphasizing the limited vision of “older men,” Roosevelt asked Congress for power to name an additional Justice when one aged 70 did not resign, until the Court should have 15 members. (Six were already over 70; Louis D. Brandeis was 80). Roosevelt said the Court needed help to keep up with its work.

Even staunch New Dealers boggled at this plan; it incurred criticism as sharp as any the Court had ever provoked. Chief Justice Charles E. Hughes calmly pointed out that the Court was keeping up with its work. And in angry editorials and thousands of letters to Congress the public protested the very idea of “packing” the Court.

Before the President revealed his plan, five Justices had already voted to sustain a state minimum-wage law in a case from Washington; on March 29, the Court announced that the law was constitutional.

On April 12, Chief Justice Hughes read the majority opinion in National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation. It upheld the Wagner Act, the first federal law to regulate disputes between capital and labor. Hughes gave interstate commerce a definition broader than the Jones & Laughlin domain—mines in Minnesota, quarries in West Virginia, steamships on the Great Lakes. Although the case turned on a union dispute at one plant in Pennsylvania, he said, a company-wide dispute would paralyze interstate commerce. Congress could prevent such evils and protect union rights. Under these two rulings, Congress and the states were free to exercise powers the Court had denied just a year before. Stubbornly the “four horsemen” dissented. But Willis Van Devanter announced that he would retire. By autumn the fight over the Court was a thing of the past.

As Lincoln said in 1861, the people would rule themselves; they would decide vital questions of national policy. But, as firmly as Lincoln himself, they disclaimed “any assault upon the Court.” In one of the Supreme Court’s greatest crises, the people chose to sustain its power and dignity.

Decisions changed dramatically in the “constitutional revolutions” of 1937. So did the Court when President Roosevelt made appointments at last. In 1937 he named Senator Hugo L. Black; in 1938, Solicitor General Stanley Reed; in 1939, Felix Frankfurter and William O. Douglas, Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

New problems tested the Court as it was defining civil liberties. Danger from abroad made the case for patriotism and freedom in America more urgent; in the “blood purge” of 1934, Adolf Hitler had announced, “I became the supreme judge of the German people.”

Under God’s law, the Commandments in the Book of Exodus, members of Jehovah’s Witnesses refuse to salute a flag.

When Lillian and William Gobitas (misspelled “Gobitis” in the record), aged 12 and 10 in 1935, refused to join classmates in saluting the Stars and Stripes, the Board of Education in Minersville, Pennsylvania, decided to expel them for “insubordination.” With help from other Jehovah’s Witnesses and the American Civil Liberties Union, their father sought relief in the federal courts. The district court and the circuit court of appeals granted it. In 1940 the school board turned to the Supreme Court.

Considering the right of local authorities to settle local problems, eight Justices voted to uphold the school board’s “secular regulation.” Justice Felix Frankfurter wrote the majority opinion. He told Justice Stone that his private idea “of liberty and toleration and good sense” favored the Gobitas family, but he believed that judges should defer to the actions of the people’s elected representatives.

Hitler’s armies had stabbed into France when Frankfurter announced the Court’s ruling on June 3, 1940; Stone read his dissent with obvious emotion, insisting that the Constitution must preserve “freedom of mind and spirit.”

Law reviews criticized the Court for setting aside the issue of religious freedom. Jehovah’s Witnesses suffered violent attacks around the country; many states expelled children from school for not saluting the flag.

In 1940, Attorney General Frank Murphy came to the bench; Senator James F. Byrnes of South Carolina, in 1941. When Hughes retired that year, Roosevelt made Harlan Fiske Stone Chief Justice and gave his seat as Associate to Attorney General Robert H. Jackson. How the “new Court” would meet old problems soon became clear.