Melville W. Fuller succeeded Morrison R. Waite as Chief Justice in 1888. In 1891, Congress passed a law that gave each circuit a court of appeals with power to make a final decision in a great many cases. This law also ended the Justices’ trips on circuit duty. Before long the Supreme Court was keeping up with its schedules. But as new laws regulated business and working conditions, and suits challenging these laws reached the courts, overloaded dockets plagued the Justices once again.

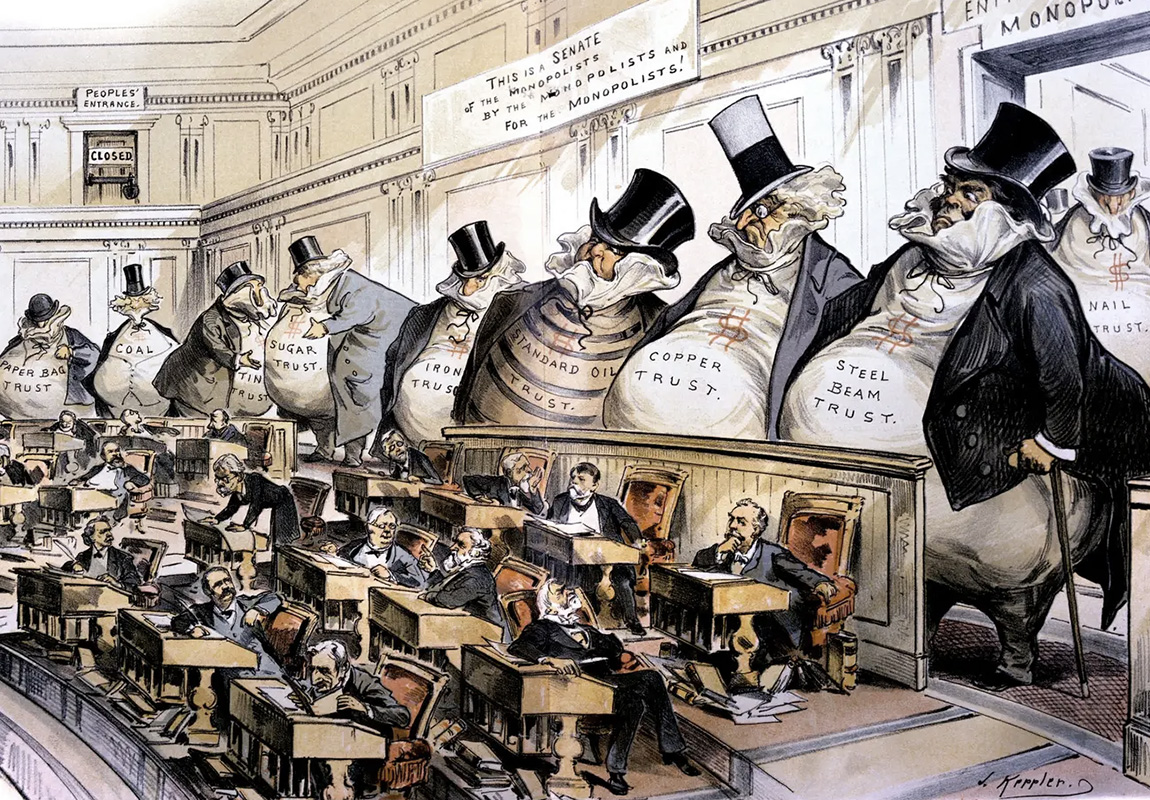

Congress had passed the Sherman Anti-Trust Act in 1890. But time proved that the legislatures were not to be the “exclusive judge.” The Supreme Court began to set new limits on state power, although it did not flatly overrule the Granger decisions.

The Court also checked Congressional power. In 1895, a depression year, critics charged that the Court let property rights govern law. Of the Court that had decided Munn v. Illinois in 1877, only Justice Stephen J. Field survived.

When the Court decided its first antitrust case, the government lost its suit against a company controlling some 98 percent of all sugar refined in the United States. The Court conceded that the trust had a monopoly on making “a necessary of life” but denied that it had a direct effect on interstate commerce. This ruling left the Sherman Act weak, the trusts as strong as ever.

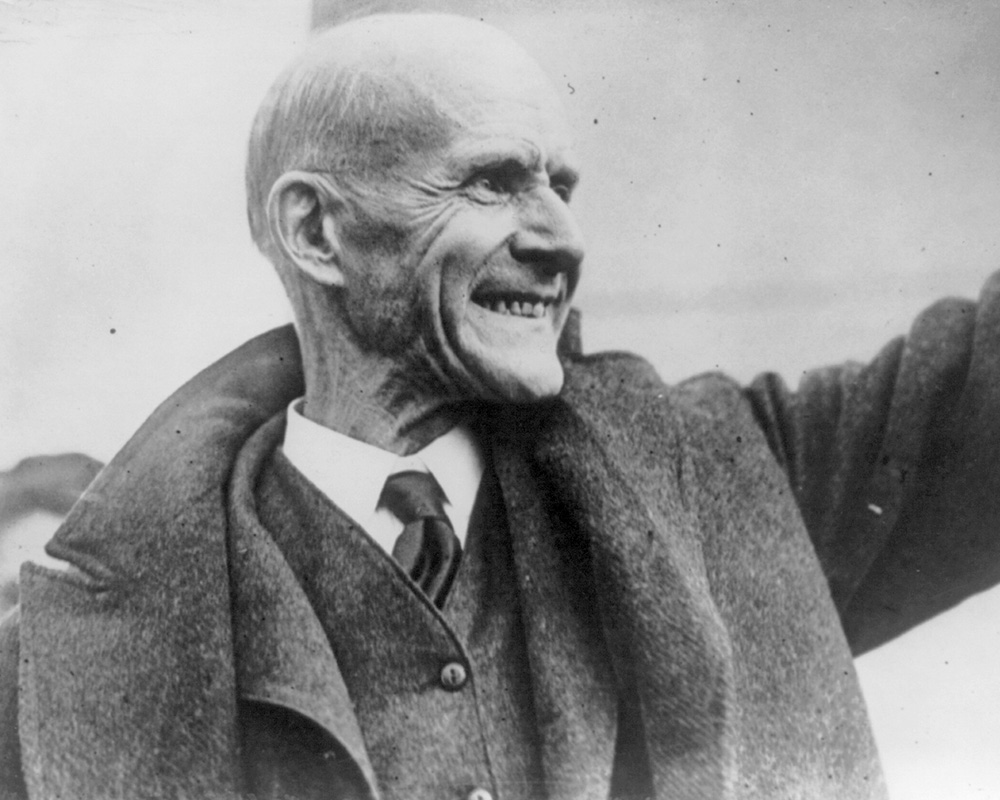

In another case, the Court incurred the wrath of unionized labor. Federal judges, under the Sherman Act, had issued a sweeping injunction against union leaders of the Pullman strike in 1894. Jailed for contempt of court, Eugene V. Debs applied to the Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus; the Justices denied it unanimously.

In a third case, the Court heard argument on a new federal income tax law, which took 2 percent of all incomes over $4,000. Famous lawyers prophesied communism, anarchy, and despotism if the law survived. With one Justice ill, the rest divided four to four on most of the law’s provisions. After reargument a five-to-four vote made the entire law unconstitutional.

Bluntly, the dissenters called this decision “the most disastrous blow ever struck at the constitutional power of Congress,” “a surrender of the taxing power to the moneyed class.” John Marshall Harlan (whose grandson of the same name was to serve on the Court in the 20th century) spoke out so sharply that the New York Sun called his “tone and language more appropriate to a stump address.”

On the stump, William Jennings Bryant said the Court stood with the rich against the poor; other political figures took up the charge. By 1913, though, the Sixteenth Amendment would make the income tax constitutional after all.

To enforce segregation by color, southern states had begun passing Jim Crow laws, to require equal but separate passenger cars on trains. Homer Adolph Plessy challenged the Louisiana law in 1892, and took his case to the Supreme Court. Its option cited many state precedents to show the “reasonableness” of such laws, and found nothing to stamp “the colored race with a badge of inferiority.” Southern-born Justice Harlan dissented again.

“Our Constitution is color-blind,” he wrote. “In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.” Still, the separate-but-equal doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson controlled the law for years.

The Spanish-American War gave the United States several heroes, including Col. Theodore Roosevelt; many islands, including Puerto Rico and the Philippines; and one baffling question: Does the Constitution follow the flag? Across the American West, it always had; pioneers took their citizenship with them, and new states joined the Union as equals.

These new islands—separate by ocean, alien by culture—seemed unfit for self-government or statehood. But the Constitution said nothing about colonies of subject peoples, unequal before the law.

In the famous “Insular Cases” the Supreme Court worked out a constitutional status for the new possessions; in effect and by necessity, the Court made law as it went along. Spectacular as the subject was, the Justices were doing the duty of every judge, applying the generalities of law to the demands of the specific case.

In 1898, a case involving cast-iron pipe ushered in a decade of dramatic “trust-busting.” Circuit Judge William Howard Taft carefully distinguished the case of the Addyston Company and other pipe manufacturers from the sugar-trust case. In the present case, he explained, the facts were different.

These companies conspired to fix prices, said Taft, before they agreed with their customers in 36 states to deliver shipments of pipe; therefore they were within interstate commerce and the power of Congress. Price fixing restrained trade as surely as pipe contained oil, and Congress had passed the Anti-Trust Act to release trade. Free enterprise, Taft insisted, meant free competition.

When the Supreme Court affirmed Taft’s ruling, other judges had a new precedent to follow and the Sherman Act a new vitality.

Energy personified, Theodore Roosevelt became President after William McKinley’s assassination, and faced what he called the “absolutely vital question”—whether the United States Government had the power to control the giant corporations of the day.

Money personified, the magnificent J. P. Morgan dominated finance, the Northern Pacific and other railroads, and the billion-dollar U.S. Steel Corporation; his ally James J. Hill had the Great Northern line. E. H. Harriman, with his Southern Pacific and Union Pacific routes and his friends in Standard Oil, had challenged Morgan and Hill for control of a railroad into Chicago.

After a fight that wrecked the stock market, the three agreed to combine forces. They organized a holding company, a New Jersey corporation called Northern Securities, and leaned back to enjoy their monopoly on transportation in the Northwest.

Roosevelt ordered the Attorney General to enforce the Sherman Act against them. In the Supreme Court their lawyers argued that only New Jersey could regulate a New Jersey corporation, that stock transactions were not within interstate commerce, that having power did not amount to abusing it.

Justice Harlan read the Court’s opinion in March 1904, to a crowded courtroom and an anxious country. New Jersey did not have Congress at its mercy, he ruled; he called the point about stocks a mere straw man; and Congress, he said bluntly, meant to prevent the “mere existence” of such trusts. If the company was secure the Northwest was not: “the entire commerce of the immense . . . part of the United States between the Great Lakes and the Pacific at Puget Sound will be at the mercy of a single holding corporation. . . .” As the court below had ordered, the Northern Securities Company must be dissolved.

After this victory and others, the government attacked the Standard Oil empire. More than ten states had moved against it under their own antitrust laws by 1906, when federal attorneys filed suit under the Sherman Act. After 15 months of testimony that filled 21 printed volumes, federal judges in St. Louis ordered the oil trust broken up.

“Unreasonable, unnecessary and arbitrary,” a violation of liberty under the Fourteenth Amendment—thus five members of the Supreme Court held a New York law unconstitutional. This law said bakers must not work more than 10 hours a day or 60 hours a week.

Joseph Lochner had a bakery in Utica, and New York fined him $20 for overworking Frank Couverette. For a second offense, he drew $50 in fines or 50 days in jail. His case reached the Court in 1905.

States, ruled Justice Rufus W. Peckham, must not pass such laws, “mere meddlesome interferences” to keep grown men from taking care of themselves. States have a “police power” to protect the public, but they may not limit such individual rights as liberty of contract: A worker must be free to make his own contract with his employer.

Justice Harlan dissented, citing evidence that bakers suffered eye and lung troubles, that New York might protect their health. And Oliver Wendell Holmes, who had joined the Court in 1902, dissented separately, to say that “a constitution is not intended to embody a particular economic theory,” that laws might rest on “novel and even shocking” ideas and be constitutional.

Oregon had passed a law to keep women from working more than 10 hours a day in factories and laundries. Curt Muller, owner of a laundry in Portland, Oregon, was convicted of breaking it; he fought his conviction through state courts to the Supreme Court, relying on Peckham’s opinion in Lochner v. New York. He also claimed that the Oregon statute could not meet the Constitution’s demand for “due process of law.”

Historically, that had meant “a fair trial.” But judges were using it to protect property from laws they found unreasonable.

One reform group wanted the best possible lawyer for Oregon’s case. Joseph H. Choate of New York turned it down; he didn’t see why a “big husky Irishwoman should not work more than ten hours if she so desired.” A famous corporation lawyer in Boston accepted—Louis D. Brandeis.

Studying Peckham’s opinion in the Lochner case, Brandeis considered its reference to “common knowledge” that baking was a healthy trade. Boldly and shrewdly, he devoted only two pages of his brief to legal points; one hundred cited facts from doctors, health officers, and factory inspectors to show that overworked women fell ill, turned to drink, bore sickly children and then neglected them.

No one had ever submitted such a brief to the Court. But the Justices accepted it, and praised him for it in their unanimous decision to uphold the law of Oregon.

“When an evil is a national evil, it must be cured by a national remedy,” cried Senator Albert J. Beveridge of Indiana. Reformers were demanding change in politics, business, society in general; in response, Congress was assuming a “police power” for the whole country.

Disturbed by reports of filth in meat-packing plants, it passed pure good and drug laws. Shocked by stories of the “white slave trade,” it passed the Mann Act. The Supreme Court upheld these laws, and others.

After Chief Justice Fuller’s death in 1910, President Taft broke tradition by choosing an Associate Justice, Edward Douglass White, for Chief.