The United States Constitution called for a Supreme Court and a federal judiciary, but left it to Congress to spell out the details. Congress did so in the Judiciary Act of 1789. Connecticut’s Oliver Ellsworth — later to serve four years as Chief Justice — led the drafting-in committee. The law created 13 district courts in principal cities, with one judge apiece, and three circuit courts to cover the other areas of the eastern, middle and southern United States. Above these it set a Supreme Court, with a Chief Justice and five Associate Justices, as the only court of appeals.

For the first Chief Justice, President George Washington picked John Jay, New-York-born statesman and diplomat. The President weighed sectional jealousies and personal ability in selecting Associate Justices — John Blair of Virginia, William Cushing of Massachusetts, James Wilson of Pennsylvania, James Iredell of North Carolina, and John Rutledge of South Carolina. All had helped establish the Constitution.

But only three of the Justices had reached New York, a temporary capital city, in 1790, when the Court convened for the first time. Required by law to sit twice a year, it began its first term with a crowded courtroom and an empty docket. Appeals from lower tribunals came slowly; for its first three years the Court had almost no business at all.

Spectators at early sessions admired “the elegance, gravity, and neatness” of Justices’ robes. But when Cushing walked along New York streets in the full-bottom professional wig of an English judge, little boys trailed after him and a sailor called, “My eye! What a wig!” Cushing never wore it again.

In 1791, the Court joined Congress and the President in Philadelphia; it heard discussions of lawyers’ qualifications but little else. Still, other duties exhausted the Justices. The Judiciary Act of 1789 required them to journey twice a year to distant parts of the country and preside over circuit courts. For decades they would grumble, and hope Congress would change this system; but Congress meant to keep them aware of local opinion and state law.

Stagecoaches jolted the Justices from city to city. Sometimes they spent 19 hours a day on the road. North of Boston and in the South, roads turned into trails. Justice Iredell, struggling around the Carolinas and Georgia on circuit, and hurrying to Philadelphia twice a year as well, led the life of a traveling postboy. Finding his duties “in a degree intolerable,” Jay almost resigned. Congress relented a little in 1793; one circuit trip a year would be enough.

Sensitive issues appeared in some of the Court’s first cases. Its decision in Chisholm v. Georgia shocked the country. During the Revolution, Georgia had seized property from men loyal to the Crown. With a pre-Revolution claim on such an estate, two South Carolinians asked the Court to hear their suit against Georgia. It agreed, saying the Constitution gave it power to try such cases. But when the day for argument came in 1793, Georgia’s lawyers did not appear. The Court gave its decision anyway, in favor of the South Carolinians.

Georgia raged; other states took alarm. They were trying to untangle finances still snarled from the war. If they had to pay old debts to “Tories” they might be ruined. They adopted the Eleventh Amendment, forbidding any federal court to try a lawsuit against another state by citizens of some other state. Thus the people overruled the Supreme Court for the first time, and established a far-reaching precedent of their own. They would give the ultimate decision on constitutional disputes.

War between Britain and France brought two more basic precedents. President Washington was working desperately to keep the United States neutral and safe; he sent the Court 29 questions on international law and treaties, and begged for advice. The Justices politely but flatly refused to help. Under the Constitution, they said, they could not share executive powers and duties, or issue advisory opinions.

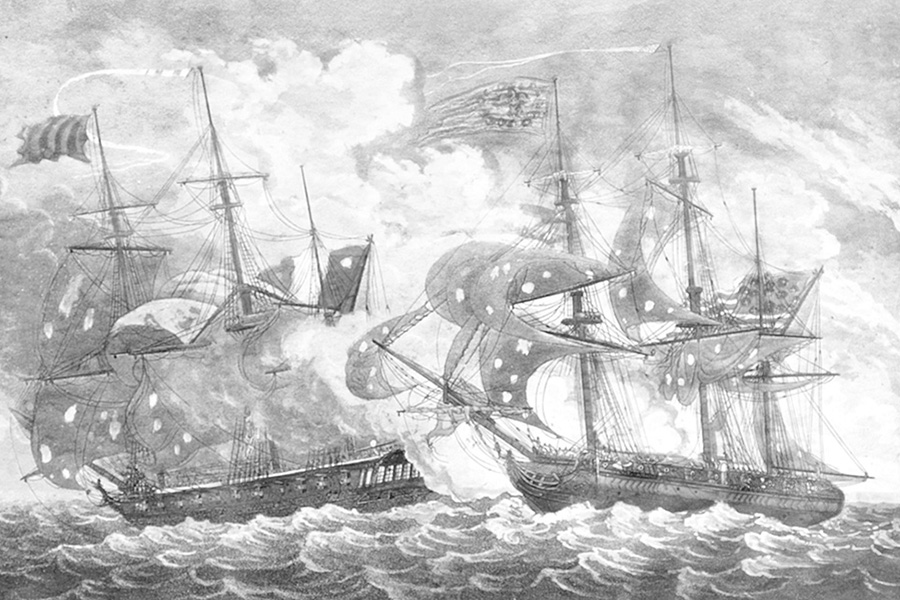

To this day, the Supreme Court will not give advice; it speaks only on the specific cases that come before it. But by its decision in Glass v. Sloop Betsey, in 1794, the Court did defend neutral rights and national dignity. Defying the President’s neutrality proclamation, French privateers were bringing captured ships into American ports. There French consuls decided if the ships were to be kept as lawful prize.

Betsey, Swedish-owned, had American cargo aboard when the French raider Citizen Genet caught her at sea and took her to Baltimore. Alexander S. Glass, owner of a share of the cargo, filed suit for his goods, but the district court in Maryland ruled that it could not even hear such cases.

With the prestige of the country at stake, the government quickly appealed to the Supreme Court. Try the case and give satisfaction, the Justices told the Maryland court; foreign consuls would not decide American claims. Europe heard this decision; and the United States became, as Washington hoped, “more respectable.”

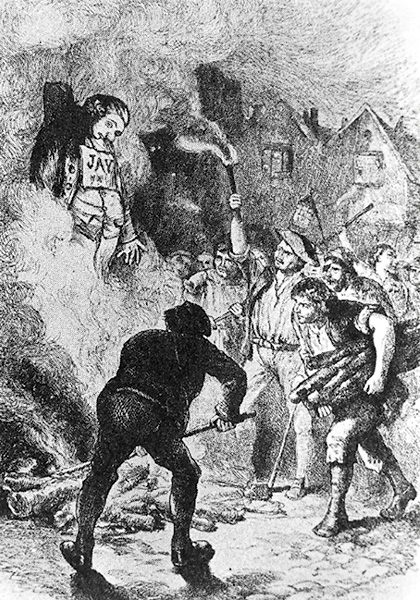

Old debts and grudges were troubling relations between the United States and Great Britain. President Washington sent Chief Justice Jay to London as a special minister to settle the quarrels, and Jay negotiated a treaty. When he returned, New York elected him Governor, and he resigned from the Court.