In 1972 Earl Warren told one of his favorite anecdotes at a retirement dinner for Bessie Margolin, a Labor Department lawyer who was wrapping up an illustrious career as an oral advocate. An expert on the Fair Labor Standards Act, she had argued 24 times before the Supreme Court. The former chief justice used the occasion to recall how daunting his first experience had been arguing before the high bench:

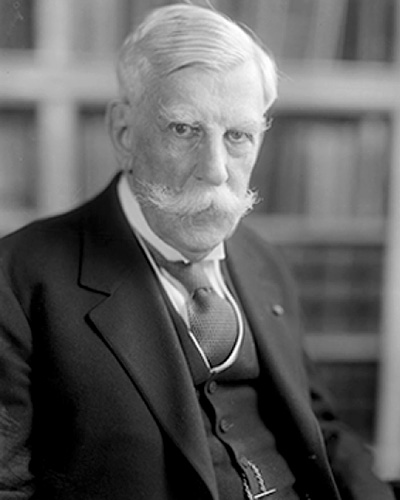

The image of these two Supreme Court luminaries facing each other from bench to bar is compelling. The venerable Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., age 90, would have strained to hear to the California attorney, age 40, make his case. One might imagine that an invisible baton was tossed from the elderly judge who had championed First Amendment rights to the young prosecutor who would, as chief justice, expand civil liberties. A reexamination of this incident is thus in order.

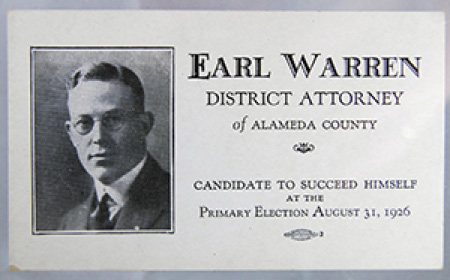

As assistant district attorney of Alameda County and an experienced litigator, Warren was assigned the case, which required defending an easement on railroad property, under which the county had a right-of-way since 1859. Warren rode the rails to Washington to argue Central Pacific Railway v. Alameda on Thursday, January 7, 1932. Three days later, on Sunday afternoon, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes called on Holmes in his study to coax him to resign. Holmes’s health had noticeably deteriorated since the summer. After consulting with Justice Louis D. Brandeis, the Chief Justice had decided it was time to undertake the delicate task. Holmes, who had served on the high court for 29 years, was obedient.

The condition of my health makes it a duty to break off connections that I cannot leave without deep regret after the affectionate relations of many years and the absorbing interests that have filled my life. But the time has come and I bow to the inevitable. I have nothing but kindness to remember from you and from my brethren. My last word should be one of grateful thanks.

He postdated the letter so he could read his last opinion from the bench the following day, albeit in a faltering, barely audible tone. On January 12, President Hoover officially accepted resignation of the Justice from Beacon Hill. A month later, the Court ruled unanimously in favor of Alameda County. Holmes’ successor, Benjamin Cardozo, had been nominated but not yet confirmed.

As chief justice from 1953 to 1969, Warren came to revere Holmes’ writings. He relished recounting the episode of the first time he set foot in the Supreme Court…and scared away his idol. From time to time, Warren would visit the old Supreme Court Chamber in the Capitol where he had argued his case in order to “commune silently with his predecessors.” Holmes was no doubt foremost on his mind.

- ABOUT THE SOCIETYMembers support the Society’s efforts to increase awareness of the Court’s contributions to our nation’s constitutional heritage. Benefits include: Court history publications, special event invitations, discounts.

- PROGRAMS & EVENTSSCHS sponsored events cover Supreme Court history themes, from early landmark figures and cases such as McCullough, to civics, labor, women’s rights, immigration, Constitutional controversies.

- PUBLICATIONS & MEDIADocumentaries covering landmark points on the timeline of Supreme Court history, including: FDR’s court packing controversy, the contested 1876 election + John Marshall & Marbury v. Madison.

- CIVICS EDUCATION

Visit the Supreme Court Historical Society’s CIVICS website to learn about the history and cases of the Supreme Court of the United States and gain insights into key figures associated with the Court.

- JUSTICES & THE COURT

A timeline of Supreme Court history, including the Marshall and Warren Courts + landmark cases: West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette, and significant rulings in women’s rights court cases.

- THE GIFT SHOP

Search SUPREMECOURTHISTORY.ORG