“My gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life.” John Adams, President

Marshall skillfully asserted the Court’s mightiest power and dignity in its first great crisis. In Congress, the lame-duck Federalists had passed a law to reduce the Court’s membership to five (one less Justice for a Republican President to name). Abolishing circuit duties for the Justices and providing other reforms, this law set up new circuit courts with 16 judges. Before leaving office, Adams had quickly named his judicial appointees — the famous “midnight judges.” Enraged, one Republican from Kentucky called Adams’s tactics “the last effort of the most wicked, insidious and turbulent faction that ever disgraced our political annals.”

Jefferson took the oath of office on March 4, 1801. Without precedents and with passions running high, the Presidency and the Congress passed for the first time from one party to another. And some citizens were afraid that the judiciary was in mortal danger.

Soon after his Inauguration, Jefferson wrote that the Federalists had “retreated into the judiciary as a stronghold, the tenure of which renders it difficult to dislodge them.”

But the Republicans repealed the lame-duck Judiciary Act, while horrified Federalists lamented, “the Constitution has received a wound it cannot long survive,” and “the angels of destruction are making haste.”

Meanwhile William Marbury of Washington went straight to the Supreme Court, looking for a commission as justice of the peace for the District of Columbia. Adams had appointed 42 such officials, the Senate frantically confirmed them, and Adams sat at his desk until late on his last night in office to sign their commissions. Then a messenger rushed the papers to the State Department for Marshall, still acting as Secretary, to affix the great seal of the United States. In the confusion some of the commissions went undelivered, Marbury’s among them.

In December 1801, Marbury applied to the Court for a writ of mandamus ordering James Madison, the new Secretary of State, to give him his commission. The Court agreed to hear the case — a bold action, for rumor was saying the Justices “must fall” by impeachment. Then the Republican Congress repealed the Judiciary Act of 1801, which mandated sessions in December and June, and eliminated the August Term of the Court. As a result, the Justices did not sit from April 1802 to February 1803, when they heard argument in Marbury’s case.

If the Court ordered Madison to produce that commission, he could simply ignore the order; President Jefferson would defend him. If the Court denied Marbury’s right to his commission, Jefferson could claim a party victory. Either way the Court’s prestige — and perhaps its members — must fall.

Marshall found an escape from his dilemma. He announced the decision on February 24, and proclaimed the most distinctive power of the Supreme Court, the power to declare an Act of Congress unconstitutional. Point by point he analyzed the case. Did Marbury have a legal right to his commission? Yes. Would a writ of mandamus enforce his right? Yes. Could the Court issue the writ? No.

Congress had said it could, in the Judiciary Act of 1789. It had given the Court an original jurisdiction in such cases — power to try them for the first time. But, said Marshall triumphantly, the Constitution defined the Court’s original jurisdiction and Congress could not change it by law. Therefore that section of the law was void. Marshall declared for all time the supremacy of the Constitution over any conflicting law. Other judges had said as much, but Marshall added: “It is, emphatically, the province and duty of the judicial department, to say what the law is.”

In renouncing a minor jurisdiction he asserted a great one, perhaps the greatest in the long annals of the law. The Supreme Court’s power as interpreter of the Constitution rests on this precedent to this day.

A few days after the decision in Marbury v. Madison, the Court again amazed the Jeffersonians. They had passed a Judiciary Act in Congress, restoring the Court’s old membership and circuit duties. The Justices ruled that it was constitutional and for a while talk of impeachment died down.

“Oyez! Oyez! Oyez! . . . the grand inquest of the nation is exhibiting to the Senate . . . articles of impeachment against Samuel Chase, Associate Justice. . . .” The Supreme Court was on trial; if Chase fell, Marshall might be next.

Feared as a “ringleader of mobs, a foul mouthed and inflaming son of discord” when he led the Sons of Liberty in 1765, Chase was “forever getting into some . . . unnecessary squabble” as a Judge 40 years later. He campaigned openly for Adams. On circuit he tried Republicans without mercy. In 1803 he told a Baltimore grand jury that “modern doctrines” of “equal liberty and equal rights” were sinking the Constitution “into a mobocracy, the worst of all popular governments.”

His enemies saw their chance. The House of Representatives voted to bring him before the Senate for trial, charging that his partisan behavior–in and out of court–amounted to “High Crimes and Misdemeanors” under the Constitution.

Vice President Aaron Burr had arranged a special gallery for ladies when the “grand inquest” opened on February 4, 1805. Burr had killed Alexander Hamilton in a duel and New Jersey wanted him for murder, but he presided sternly, rebuking Senators who were eating cake and apples. “We are indeed fallen on evil times,” said one. “The high office of President is filled by an infidel; that of Vice-President by a murderer.”

Representative John Randolph of Roanoke, the brilliant, erratic Virginian, fought to prove Chase unfit for the Court. Luther Martin of Maryland, who could hold more law and more brandy than any other attorney of his time, led Chase’s defense. Marshall and 51 other witnesses testified.

Amid “a vast concourse of people . . . and great solemnity,” the Senators acquitted Chase on March 1. Jefferson called impeachment of Justices “a farce which will not be tried again,” and he was right.

For all his differences with the Republicans, John Marshall was no son of discord. Born in a log cabin near Germantown, Virginia, in 1755, he grew up near the frontier, with some tutoring for an education. He fought as an officer in the Revolution, almost freezing at Valley Forge.

After the war he practiced law, and became the leading Federalist of his state. As a young attorney and an aging Chief Justice, he was sloppily dressed and wonderfully informal out of court, fond of spending hours with friends in taverns, law offices, and drawing rooms. Even in his sixties, Marshall was still one of the best quoits players in Virginia.

When the Court met in Washington, the Justices stayed in a boardinghouse – – the trip was too long, the session too short for their wives to accompany them — and Marshall’s geniality brightened their off-duty hours.

Justice Joseph Story handed down a tale still told at the Court. On rainy days the Judges would enliven their conferences with wine; on other days Marshall might say, “Brother Story, step to the window and see if it doesn’t look like rain.” If the sun was shining, Marshall would order wine anyway, since “our jurisdiction is so vast that it might be raining somewhere.”

Congress expanded that domain in 1807, creating a new circuit for Kentucky, Tennessee, and Ohio, and adding a seat to the Court. Jefferson appointed Thomas Todd, who had helped create the State of Kentucky out of his native Virginia.

Life in Washington went on peacefully for months during the War of 1812. “Mrs. Madison and a train of ladies” visited the Supreme Court one day in early 1814, just as William Pinkney of Maryland, one of the country’s most celebrated lawyers, was ending an argument; “he recommenced, went over the same ground, using fewer arguments, but scattering more flowers.”

Rudely interrupting such diversions, the British arrived in August and burned the Capitol. Congress found shelter in the makeshift “Brick Capitol” where the Supreme Court building stands today.

The Court, forced to shift for itself, met for a while in a house on Pennsylvania Avenue. Then it got temporary space in the Capitol. In 1819 it returned to its own semicircular room below the Senate Chamber.

“A stranger might traverse the dark avenues of the Capitol for a week,” reported a visitor from New York, “without finding the remote corner in which Justice is administered to the American Republic. . . .”

Strangers traversing the Republic had other troubles. “I passed away my 20-dollar note of the rotten bank of Harmony, Pennsylvania, for five dollars only,” a disgusted traveler complained at Vincennes, Indiana. State-chartered banks, private banks, towns, sawmills, counterfeiters — all issued notes freely. “Engravings,” a Scotsman called them; no law required anyone to accept them at face value as legal tender. Everyone suffered from this chaos.

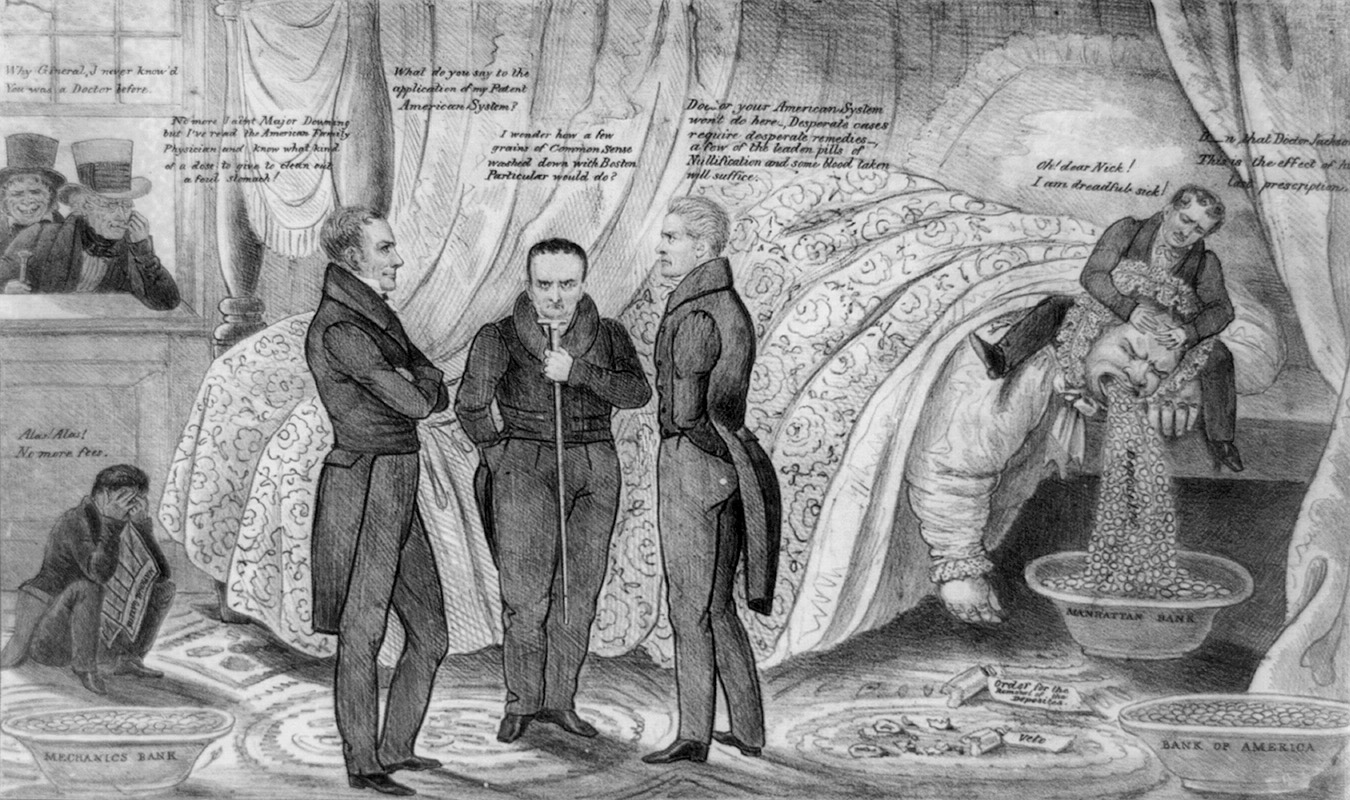

Congress had chartered the second Bank of the United States in 1816 to establish a sound national currency, to issue notes it would redeem in gold or silver. By law, the government owned a fifth of the Bank’s stock and named a fifth of its directors; private investors had the rest. Unscrupulous characters got control of the Bank and mismanaged its affairs.

In the South and West, where “engravings” flourished, the Bank’s branches made bad loans until the home office at Philadelphia issued new orders in August 1818: Call in those loans. Don’t accept any payments but gold and silver or our own notes. Panic spread. Local banks demanded payment on their own loans, and refused to extend credit; people scrambled for money they couldn’t find; land went for a song at sheriffs’ auctions; shops closed; men who lost their last five dollars said bitterly, “the Bank’s saved and the people are ruined.”

State legislators decided to drive the Bank’s branches out of their domain. Maryland passed a tax law giving the Baltimore branch its choice: pay up handsomely or give up and leave. The branch ignored it. Maryland sued the cashier, James McCulloch, and won in its own courts. McCulloch took his case- – that is, the Bank’s- – to the Supreme Court where argument began on February 22, 1819.

Splendid in his blue coat with big brass buttons, Daniel Webster spoke for the Bank- – Congress has power to charter it; Maryland has no power to tax it, for the power to tax involves a power to destroy; and never under the Constitution, may the states tax the Union into destruction.

Luther Martin, Maryland’s Attorney General, argued for his state. Where does the Constitution say Congress has power to create a national bank? He asked. Nowhere! He thundered. It lists specific powers, and making banks is not one of them. Mr. Webster says it implies such a power. Nonsense!

For the Court, Marshall defined the controversy: “a sovereign state denies the obligation, of a law . . . of the Union.” An “awful” question, but “it must be decided peacefully.” Because the Union is “emphatically, and truly, a government of the people,” it must prevail over the states. To specific powers of Congress, the Constitution adds powers to make all laws “necessary and proper” for carrying them into effect.

Marshall invoked “letter and spirit” to give that clause its meaning: “Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution,” and Congress may use “all means which are appropriate . . . which are not prohibited.” So the Bank was constitutional; no state might tax it. Maryland’s law was “unconstitutional and void.”

The Court’s ruling settled the conflict of law but not the political fight over the Bank’s power and states’ rights. Virginia’s legislature made a “most solemn protest” against the decision in McCulloch v. Maryland; Ohio officials took money by force from one Bank branch. Not until President Andrew Jackson vetoed the Bank’s recharter did that controversy die down.

States’ rights against the powers of the Union – the issue became more explosive than ever when the country faced its first great quarrel over slavery, in 1819. Southerners in Congress threatened secession and civil war; a Georgian foresaw “our houses wrapt in flames.” When the House was discussing a bill to make Missouri Territory a state, a New York Representative suggested that Congress forbid slavery there. Southerners warned, “the Union will be dissolved.” The reply flashed, “let it be so!”

For months the furious debate went on. Then, in February 1820, Senator Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois offered a compromise: Maine to be a free state, Missouri a slave state, and the rest of the Louisiana Purchase north of 36′ 30′ free soil forever. Henry Clay supported the plan; early in March, President James Monroe signed the laws to carry it out. Apparently the crisis was over.

But trouble flared again as Congress debated Missouri’s proposed constitution and states’ rights in general, and what had been a trivial criminal case quickly became a rallying point for states’ rights advocates and proponents of secession. In Norfolk, Virginia, P. J. and M. J. Cohen were charged with violating a state law by selling six tickets in a lottery established by Congress to pay for improvements in the District of Columbia. The law forbade all lotteries except the state’s own. A Norfolk court convicted the Cohens; they turned to the Supreme Court, pointing out that their lottery tickets were authorized by federal law.

Virginia rose in wrath. Her General Assembly declared that the Court had no jurisdiction. Her lawyers fought the Cohens’ request for a hearing. They warned the Supreme Court against “exciting the hostility of the state governments,” which would decide how long the Union should endure.

Then, in March 1821, a second compromise was reached, bringing Missouri into the Union five months later as a slave state, but with guarantees designed to protect the rights of free Negroes and mulattoes. The issues of slavery and secession subsided, eventually to be resolved in blood.

Undeterred by the impassioned controversy, Marshall gave an uncompromising ruling in Cohens v. Virginia. The Court would hear the case; it existed to resolve such “clashings” of state and Union power, to keep the national government from becoming “a mere shadow.” Insisting on the power of his Court, the Chief Justice boldly met the threat of secession and the claims of state sovereignty; he upheld the Union as the supreme government of the whole American people.

Then the Court heard argument on the merits of the case, and affirmed the sentence of the Norfolk court. The Cohens lost $100 — their fine — and costs.

Southerners fumed at Marshall’s stand in the Cohens’ case. But in 1824, for once, a Marshall ruling met popular acclaim. Huzzas from the wharves greeted the steamboat United States as she chuffed triumphantly into New York harbor, her crew firing a salute, her passengers “exulting in the decision of the United States Supreme Court.” That case was Gibbons v. Ogden.

Robert Fulton successfully demonstrated a steam-powered vessel on the Seine at Paris in 1803. With his partner, Robert R. Livingston, he held an exclusive right from New York’s legislature to run steamboats on state waters, including New York harbor and the Hudson River. In 1807 his steamer splashed up the Hudson to Albany; soon money flowed into their pockets. Anyone else who wanted to run steamboats on those waters had to pay them for the privilege; some Albany men attacked the monopoly in state courts, and lost.

In 1811 the territorial legislature in New Orleans gave the partners a monopoly on the Mississippi. Now they controlled the two greatest ports in the country.

New Jersey passed a law allowing its citizens to seize steamboats owned by New Yorkers; other states enacted monopolies and countermeasures until the innocent side-wheeler was turning into a battleship.

Meanwhile three men of property went into business, then into rages, then into court. Robert Livingston’s brother John bought rights in New York Bay; then he sublet his waters to former Governor Aaron Ogden of New Jersey, a quarrelsome lawyer. Ogden took a partner, Thomas Gibbons, equally stubborn and hot tempered.

Under an old Act of Congress, Gibbons had licensed two steamboats for the national coasting trade, and now he invoked this federal law to get a suit against Ogden before the Supreme Court.

The once obscure Supreme Court was now a focus of public interest. Ladies crowded lawyers to hear the case. Daniel Webster spoke for Gibbons on February 4, 1824; Ogden’s attorneys quoted established law and precedents for two days. But Marshall avoided shoals of precedents and veering winds of state laws to set his course by the Constitution – the clause giving Congress power to regulate commerce among the states. For the first time the Court defined these words; in them Marshall found vast new currents of national strength.

More than buying and selling, he proclaimed, commerce is intercourse among nations and states; it includes navigation. For all this rich activity Congress may make rules; if its rules collide with state restrictions the latter must sink. New York’s law went down before an Act of Congress.

State monopolies could not scuttle ships “propelled by the agency of fire.” Steamboats would be as free as vessels “wafted on their voyage by the winds.”

With monopolies swept away, steamboat trade spread fast and freely. Soon, by that precedent, steam cars on rails spread across state lines, across the continent.

Marshall watched, as changes came and went. “We must never forget,” he said, “that it is a constitution we are expounding . . . a constitution, intended to endure for ages to come, and consequently, to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs.” His actions made his words unforgettable.

When Marshall gave the Presidential oath to his cousin Thomas Jefferson in 1801, the Supreme Court was a fortress under attack. It had become a shrine when he gave the oath to Andrew Jackson in 1829.

The Court’s ruling settled the conflict of law but not the political fight over the Bank’s power and states’ rights. Virginia’s legislature made a “most solemn protest” against the decision in McCulloch v. Maryland; Ohio officials took money by force from one Bank branch. Not until President Andrew Jackson vetoed the Bank’s recharter did that controversy die down.

New crises arose during Jackson’s Administration. Marshall carried on his work, concerned for the country’s future but not for his failing health. Jay had resigned after five years, Ellsworth after four; Marshall served from 1801 until his death in 1835. When he took the judicial oath the public hardly noticed; when he died the Nation mourned him. “There was something irresistibly winning about him,” said the Richmond Enquirer and Niles’ Register, which had long denounced his decisions, said, “Next to Washington, only, did he possess the reverence and homage of the heart of the American people.”